The first time I saw The Godfather's Don Corleone, it wasn't in a movie theater. It was on Saturday Night Live.

John Belushi did an amazing impression of Marlon Brando as Corleone, and he was playing the Don in a group therapy session with Elliot Gould as the therapist. Laraine Newman was decked out in a blond wig and Valley Girl accent for the sketch from SNL's first season, dubbed "Godfather Therapy," telling Belushi's Corleone, "please reach out, man!"

(One of my favorite lines from that sketch: "Now the feds are watching me...investigating me. The ASPCA's after me about this horse thing...")

That was a measure of how much The Godfather had already permeated pop culture by 1976. Even an 11-year-old Black kid watching TV in Gary, Indiana knew about the Mob boss who made people offers they couldn't refuse.

A few years later, when I actually saw the film, I was transfixed. Not just because the movie offered an explicit look at the power and violence of gangster life – the scene where James Caan's Sonny Corleone got perforated by dozens of bullets at a toll booth gave me nightmares for a good while – but because The Godfather showed us a very specific family at a specific time in a very specific culture.

It was apparent from the movie's very first line. "I believe in America," says Amerigo Bonasera, a balding undertaker in postwar America who tells an immigrant's tale of working hard, trying to stay out of trouble and build a life for his family. Until the American justice system fails him, and he must seek help from a man whose power transcends any legal authority.

Fifty years ago, The Godfather helped prove that authenticity made a movie better. That casting a big name in an epic film wasn't as important as casting the person who best inhabits the character.

I didn't know it then, but The Godfather was setting a template for authenticity in filmmaking that would affect the careers of everyone from Martin Scorsese and The Sopranos' creator David Chase to Spike Lee and even, perhaps, younger talents like Atlanta creator Donald Glover and Ramy co-creator Ramy Youssef.

Fifty years ago, The Godfather helped prove that authenticity made a movie better. That casting a big name in an epic film wasn't as important as casting the person who best inhabits the character.

And giving audiences the sense they were watching a Mafia story rooted in the culture of Italian immigrants, who had a code imported from the old country, helped humanize the characters and make us care for them even more.

I had never met any Italian people from New York or the East Coast. But I felt I learned a little about the rhythms of their culture from watching The Godfather, even as the film kicked off a debate over whether its depictions of Italian Americans were damaging stereotypes.

Along the way, The Godfather created archetypes for telling stories about the Mafia that helped inspire some of the best films and TV shows of the modern age.

Seeking innovation through authenticity

"We're going to make a picture that's going to be Sicilian to the core. You can smell the spaghetti."

That's Robert Evans, who was head of production at Paramount Pictures in 1972, explaining in the film version of his memoir The Kid Stays in the Picture why they hired Italian-American director Francis Ford Coppola to direct The Godfather, with a mandate to bring an authentic-feeling culture to the film.

According to Evans, gangster films had failed in the past, in part, because studios cast actors like Kirk Douglas – performers who didn't look the part or know the culture (Douglas had, in fact, starred in a bomb of a gangster movie for Paramount in 1968, The Brotherhood, cited as the reason why the studio hadn't made a Mafia movie in years). Indeed, when Coppola, author Mario Puzo and producer Al Ruddy were working on casting the film, non-Italian actors like Laurence Olivier, Ryan O'Neal and Robert Redford were floated as possibilities for the cast – old school thinking from a different time.

These days, we take it for granted that Mafia movies and TV shows are filled with Italian-American culture, made by Italian filmmakers and actors. We've seen Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci in Goodfellas; De Niro in Mean Streets; James Gandolfini leading a whos who of Italian and Italian-American actors in a TV show considered one of the best series ever made, The Sopranos.

There's a dynamic that happens in TV and film, where more culturally specific and authentic stories can impact the audience in two ways. First, you get to know a subculture you might not know well, enticed by watching the kind of people you might never meet in real life reveal themselves in ways they likely never would in person. If you know the subculture, you're drawn in by identifying with the story — assuming the storytellers get the details right.

Secondly, there is always a human dimension that comes through that cultural specificity that anyone can relate to. John Singleton's 1991 film Boyz n the Hood tells an authentic tale about young Black men navigating gang violence and poverty in South Central Los Angeles. But it's also a coming-of-age story about youths choosing their paths in life and facing the consequences of their choices – something lots of people can understand.

For me, watching The Godfather brought those two thrills into sharp focus. Seeing the bright pageantry of Connie Corleone's wedding, contrasted with the dark backroom dealings of her father The Don – who must consider requests made at his daughter's nuptials. Hearing loyal aide Clemenza discoursing on the proper way to make pasta with meatballs for a house full of the family's soldiers, hiding out in the middle of a gang war. Seeing the rituals of christenings and marriages compared with the killings necessary to secure the family's success in crime.

The very specific story of a Mob family, juxtaposed by the classic tale of an aging patriarch wondering who will succeed him. And his horror when he realizes the son who was his golden child – the one positioned to find legitimate success in the world outside their crime family – is the only one who can take his place.

Avoiding stereotypes by creating authentic characters

Compelling as that story turned out to be, there were lots of groups who feared The Godfather would simply amplify stereotypes about Italian immigrants and Italian Americans. Even before filming started, the project faced criticism from a group called the Italian American Civil Rights League, led by reputed mobster Joe Colombo.

(The Offer, a limited series on Paramount+ about the making of The Godfather, details how producer Ruddy brokered a truce with Colombo – played with a blunt impatience by Giovanni Ribisi – by agreeing to have the word "Mafia" stricken from the film's script.)

Protests over the franchise have continued until the modern day, with the Italic Institute of America criticizing showings of The Godfather: Part II at an Illinois theater in 2019, saying the film embraces stereotypes about Italian criminality that have existed in America for hundreds of years. On the other hand, author Tom Santopietro argues in his book The Godfather Effect, that the film trilogy suppressed more stereotypes than it encouraged — squashing the notion of Italians as uneducated, heavily-accented simpletons.

I remember talking to a TV writer friend about issues like this years ago, when series like The Wire and The Sopranos were drawing complaints from groups with valid concerns about how the series' might stereotype Black people or Italian Americans.

The TV writer told me back then that creators' best defense is to make sure their stories center on three-dimensional characters making decisions consistent with their perspectives, humanizing them. So, in The Godfather, you're not watching a stereotypically violent mobster simply order someone killed; you're seeing Al Pacino's Michael Corleone have the brother-in-law who is regularly beating his sister – and colluding with a rival family – eliminated.

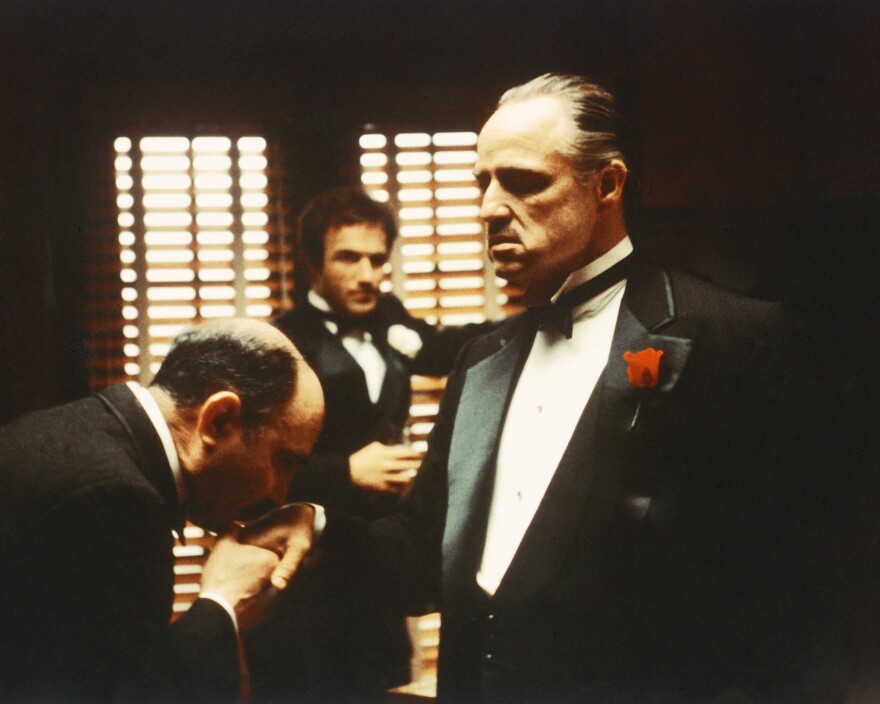

The Godfather also provides a textbook on how to elevate the antiheroic characters above the villains. Marlon Brando's Don Corleone is a man with strong values – he builds a network of "friends" with whom he trades favors. We don't see him shaking down shopkeepers for protection payments or breaking gambler's legs to get debts paid.

Also, displaying signals often used to sort antiheroes from villains for audiences, The Don is opposed to dealing drugs and doesn't reflect the racism of the times. It's a rival Mob leader who declares he doesn't mind allowing drug dealing in neighborhoods where Black people live, because "they're animals anyway, so let them lose their souls."

Small wonder that the massive success of The Godfather – and its recasting of a Mob family as a clan facing Shakespearean drama and epic challenges – reshaped how Mafia movies were told. By the time The Sopranos rolled around 27 years later, creator David Chase was pushing back against innovations in The Godfather which have become tropes – revealing his Mob boss Tony Soprano to be a merciless, philandering, sometimes racist psychopath, despite all his talk of family values and old school loyalties.

Fifty years after its blockbuster debut, The Godfather still casts a long shadow over storytelling in TV and film, fueled by its marriage of the classic gangster's story with a family drama, the immigrant's journey and lots of Italian culture.

It's a movie that reimagined how we all see the Mafia, proving that cultural authenticity is often the most powerful tool any storyteller can wield.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.