It was the absence of feathers that got conservation biologist Thor Hanson thinking about the significance of them. Hanson was in Kenya studying the feeding habits of vultures, and he noticed the advantages that vultures had relative to other birds because of their bare, featherless heads.

"Having lost their feathers allows [vultures] to remain much cleaner and more free from bacteria and parasites and disease," Hanson tells Fresh Air contributor Dave Davies.

In an effort to better understand the composition of feathers, Hanson disassembled a wren bird, which he learned how to pluck from reading The Joy of Cooking. After hours of plucking, Hanson says, he learned how the feathers are arranged, how many different types of feathers the bird has and the magnitude of feathers on a bird. He writes about the process in his new book, Feathers, which looks at the evolutionary significance of feathers in birds.

"For this tiny wren, I had well over 1,500 feathers by the time I was done — an incredible number of feathers," he says. "And it's a real testament to their importance for birds that in general, the weight of their feather coat outweighs the dry weight of their skeleton by more than 2 to 1 in most species."

One thing Hanson says he found truly remarkable is how feathers grow. While other skin coverings, such as hair, are composed of dead cells stacked on top of each other, feathers are infused with blood.

"If you injure the pin feather — the growing feather of a bird — that's quite a significant injury," he says. "It will bleed a lot. It's only after that growth is completed that the blood vessels are retracted from the base of the feather, so while it's growing, it's alive. ... Because it's so complex, you can do a lot of complex structural things with it; you can make these incredibly branched and delicate structures that have so many functions."

Hanson won the 2008 USA Book News Award for nature writing for his first book, The Impenetrable Forest: My Gorilla Years in Uganda. He is a Switzer Environmental Fellow and a member of the Human Ecosystems Study Group.

Interview Highlights

On the composition of feathers

"Feathers are a protein; they're made of keratin. It's a specific keratin to feathers, but it's similar in general to the keratin that makes up our fingernails or our hair. Keratin is a very common protein in nature because it's tough stuff. And so you find it in the skin of animals, or in these hard and horny surfaces or hair — things that have a protective function. So [the] feather protein is one that is very well-suited to feathers, because it is lightweight and very durable and very tough, and it takes color well."

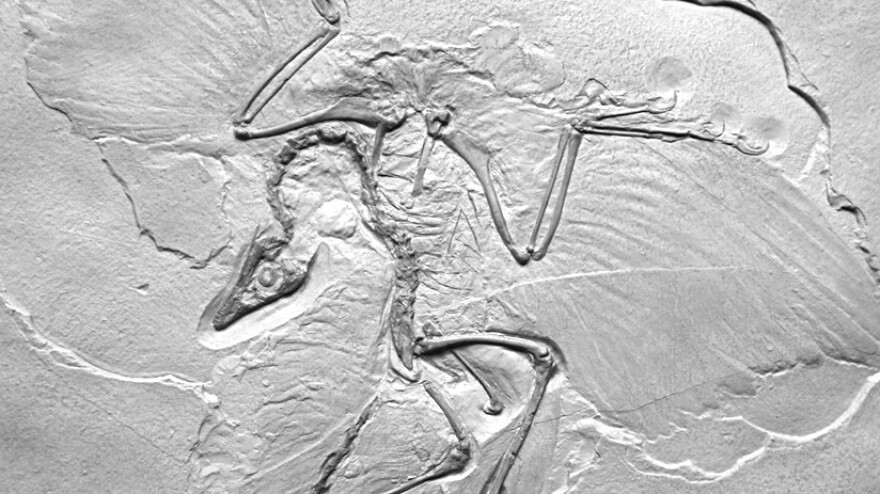

On the evolution of feathers

"There's great evidence now for feathers evolving in the theropods [meat-eating dinosaurs including Tyrannosaurus rex]. And these creatures were primarily runners — they had long, strong, overdeveloped, marathon-runner legs, and walked on two legs and ran on two legs, which freed up their arms, perhaps, by one of the theories, to be feathered and used eventually for flight. But one thing that we really believe now about the evolution of feathers is that the simplest feathers — the first feathers in the series of steps toward building a complex vein feather — were not aerodynamic. So the first uses of feathers must have been for other purposes."

On feathers as insulation

"To this day, they are the most efficient insulation known. We haven't been able to match them with synthetics, and I think it boils down to that growth process and the fact that you can make these fine, fine branching structures. The key to insulation is what they call loft — how much air can you hold in a small space? And because feathers are so beautifully and finely branched, they can hold a great deal of tiny, tiny air pockets in that branched structure. And that's what people try to mimic with synthetics, but haven't been able to match feathers for that yet, because it's difficult to manufacture finely branched structures."

On the link between feathers and flight in birds

"We do know now that flight came after the feather, and that the early stages of feathers were not aerodynamic. It's only the most advanced stages in feather evolution that have that aerodynamic structure. But ultimately the result of all of this evolution is an incredible adaptation for flight. If you look at a bird's wing, it has a particular shape that is similar to the shape you would see if you looked out the window of an airplane, and that is an airfoil-shaped wing with a curved upper surface that gives that wing a bit of extra lift in the air, and a bird wing has that shape, just as an airplane wing does. But what's amazing about a bird wing is that the individual flight feathers are also shaped like airfoils. ...

"So what you get for a bird wing is an airfoil made up of airfoils, and the bird has muscle control over all of those feathers, so it can constantly adapt and change the position of feathers and the shape of the wing to react to any change in air temperature, or wind direction, or air pressure, making it a truly incredible way to fly."

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.