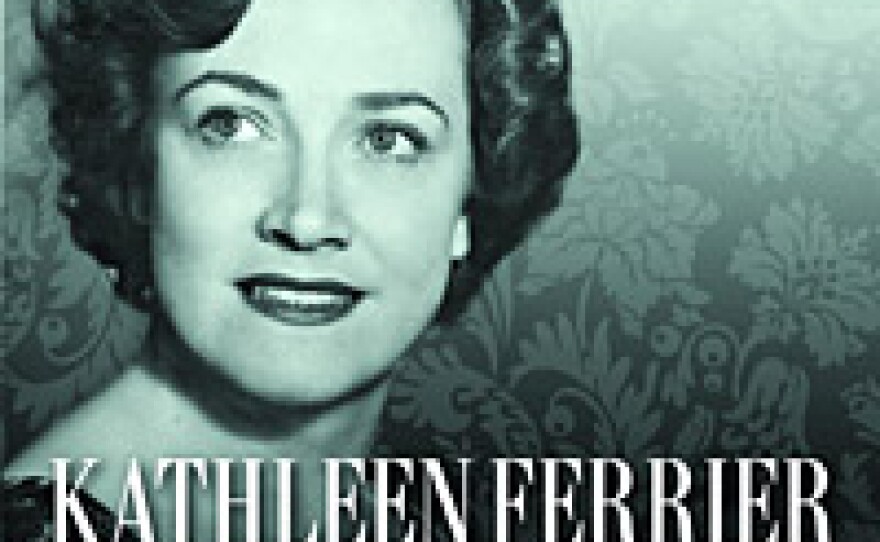

One hundred years ago, a musical marvel was born. She grew up in a tiny hamlet in the North of England, but made a huge impression on the world of classical music.

"Unique" is an overused word, yet it truly fits the sound of Kathleen Ferrier's voice. If you've never heard it, prepare to be amazed — stop reading now and click on the link below.

Her voice was a true contralto, radiant and rich with velvety purple tones reaching deep into a manly range. In addition to the sheer beauty of her sound, there's a palpable sense of communication. All the greatest singers have it — from Billie Holiday and Edith Piaf to John McCormack and George Jones — and when you hear them, it sounds like they are singing to you and you alone. Ferrier had it in spades.

To mark the 100th anniversary of her birth on April 22, 1912, Decca has issued a 14-CD Ferrier box set that includes an hour-long documentary on her life and career. It's a treasure-trove of incredible singing, from a complete recording of Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice to British folk tunes to riveting live broadcasts of songs by Schubert, Schumann and Brahms from the 1949 Edinburgh Festival.

Ferrier was an unlikely candidate to become one of classical music's most extraordinary singers. She had no upper level institutional musical training. She excelled at the piano as a kid, but her only singing took place in the bathroom of her Lancashire home. At age 14, her parents, worried by finances, took her out of school and she landed a job at the telephone exchange of the local post office.

Later she met and married a bank manager. In 1937, on a lark, she took him up on a bet that she wouldn't dare enter a regional singing competition. She took home first prize and along with it the confidence to start accepting singing engagements around Northern England.

In just a few short years, while World War II was ripping Europe apart, Ferrier's career bloomed. By war's end, she had moved to London, hired an agent, signed a recording contract and begun attracting leading figures in music, including conductors Bruno Walter and John Barbirolli and composer Benjamin Britten, who wrote for her the lead role in The Rape of Lucretia. She made her stage debut in Britten's opera at Glyndebourne in 1946.

Of all of these men Ferrier probably cherished most her time with Walter. "To learn with him the songs of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Mahler, is to feel that one is gaining knowledge and inspiration for the composer himself," she wrote in a letter. "It is very exciting and sometimes almost unbearably moving."

With Walter, Ferrier found herself on the forefront of a Gustav Mahler revival. The composer's music was banned during the war in countries occupied by Germany, and Walter, as a personal friend of the composer, was keen to bring it back.

Perhaps the greatest of the Ferrier-Walter-Mahler projects was the 1952 recording in Vienna of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth). When Mahler wrote the work's final movement, "Der Abschied" (The Farewell), he showed it to Walter, who said, "I was profoundly moved by that uniquely passionate, bitter, yet resigned and benedictory sound of farewell and departure, that last confession of one upon whom rested the finger of death." Mahler, only in his 40s, had been recently diagnosed with a heart condition that would eventually lead to his early death.

What makes this particular recording special, beyond the riveting performance by Ferrier, is the fact that she was dying of breast cancer while singing Mahler's soaring, valedictory music. Ferrier died peacefully in her sleep Oct. 8, 1953 at just 41.

It was a huge loss for Britain. Ferrier had become almost as beloved as the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II. It was an even bigger loss for music, as a voice like Ferrier's appears only very rarely. Her friends and colleagues remember her as a simple, warm person, radiant with life, obsessed with music and equipped with a bawdy sense of humor — all attributes that leap from these recordings.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.