Readers always seem to want to get closer to Emily Dickinson, the godmother of American poetry. Paging through her poems feels like burrowing nose-deep in her 19th century backyard — where "the grass divides as with a comb," as she writes in "A narrow Fellow in the Grass."

And yet the deeper one probes the poems, the more their meaning seems to recede, so that their minutiae suddenly speak for an almost inarticulable, often dark truth or wisdom at the core of things: "Zero at the Bone" is how she characterizes the more-than-fear she feels upon meeting the snake who is this poem's subject. Her images are so strange, and yet so startlingly accurate, that it's hard to believe one person could contain such contradictions. Who was this poet, really?

Until now, to fathom Dickinson, fans could make the pilgrimage to her Amherst, Mass., home, scrutinize the authenticated and contested daguerreotypes for clues and, of course, pore over her poems and letters. But now we have another way to approach the Emily who inspires and confounds us: this significant collection of facsimiles and transcriptions of late poems drafted — one might even say grafted -- on leftover envelopes.

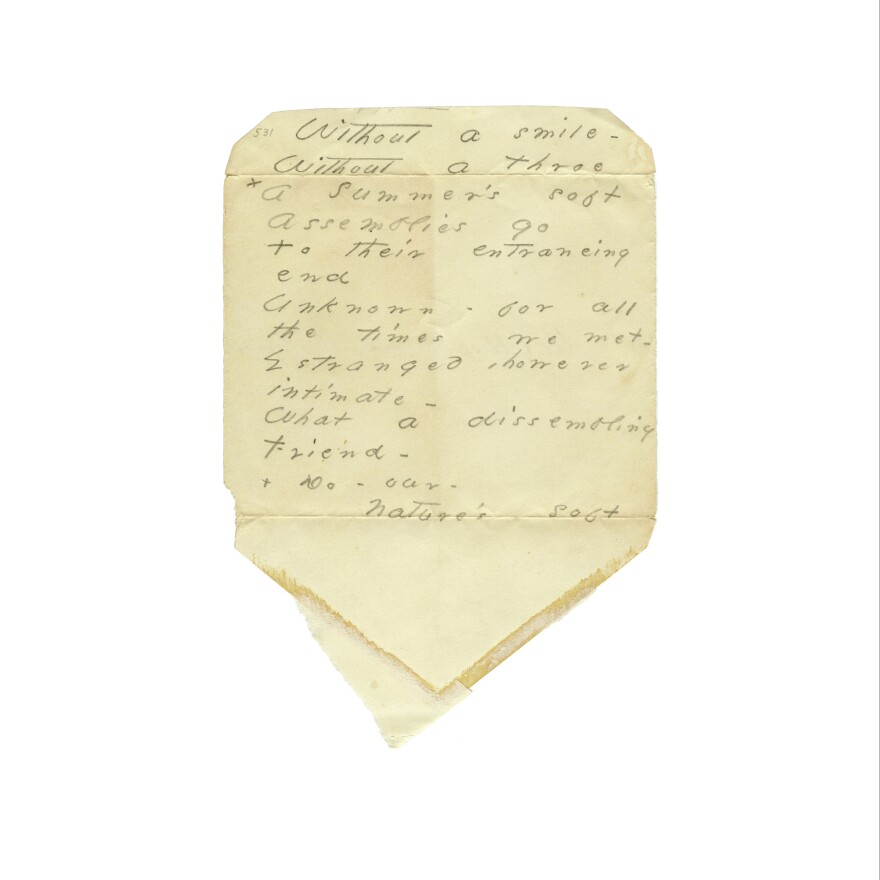

These 52 pieces were found, unbound, among Dickinson's papers, written on envelopes that had been used or addressed and unsent. They are as much works of visual as textual art, offering the chance to read into Dickinson's slanting handwriting. Her bubbly loops and long strokes suggest, to me at least, the odd confidence of one who knows the peculiar joy of refining and performing her own identity on a private stage, a bit like the names of boys or bands on the backs of middle-school notebooks.

And, if we agree with editor Marta Werner, Dickinson was playing not only with the arrangement of words in poetic lines, but the arrangement of different groups of words on different parts of these envelopes. On a folded-over lip of one envelope, she describes a "Drunken man" (who may also be dead, or almost dead), "Oblivion bending / over him," and, written slanted over the curled edge, "enfolding him / with tender / infamy." It's the medium making the metaphor here, something usually reserved for sculpture. This is poetry in 3-D.

These are late writings, probably composed after she'd sewn up the last of her famous "fascicles," the bound packets in which her poems were found after her death. So these are experiments, perhaps, begun after she'd set the bulk of her legacy in store for "immortality," one of her favorite words. Due, perhaps, to the limits these unusually shaped pages exerted on her writing, the best of these poems are among her most compressed and aphoristic. "A Pang," she writes, "is more / Conspicuous in Spring / In contrast with the / things that sing," blending colloquial and biblical speech in the kinds of enigmatic leaps that make her poems rush with wind.

The editors offer endless avenues of interpretation; the typed transcriptions of Dickinson's handwriting are superimposed atop the outlines of their corresponding envelopes, so the multidirectional layout of the text isn't lost. A series of esoteric indexes — by shape of the envelopes, by what direction they are turned, by whether or not they have "penciled divisions," for example — encourage the reader to speculate about the various relationships Dickinson may have conceived between paper and words.

It's a good season to chase after the ever-elusive Emily Dickinson. In addition to this book, there's a corresponding exhibit in Chicago; there's also a separate show in New York City, and all of the poet's online archives were recently organized into one accessible hub. This book is a rare gift for all poetry lovers. We are lucky to have more of Dickinson's ongoing "letter to the World / That never wrote to Me," an endlessly fascinating correspondence, addressed to any of us who find it — so long as we're willing to answer it with concentration and curiosity.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.