Football injuries have long been seen by some as a badge of honor. A broken sternum, a busted knee, a pierced kidney: all evidence of tenacity on the field.

But the emerging science around head injuries in football — and the long-term effects of repeated concussions – is forcing players, team owners and football fans to come to grips with the idea that the sport they love may be extracting a much higher price than anyone knew.

"It wasn't scary until some of the prominent players — guys that I knew, some of the guys that I played against — started to have this problem."

X's and O's (A Football Love Story) premieres this month at California's Berkeley Repertory Theater, exploring the tension between these medical discoveries and the insatiable demand from fans to see a hard hit.

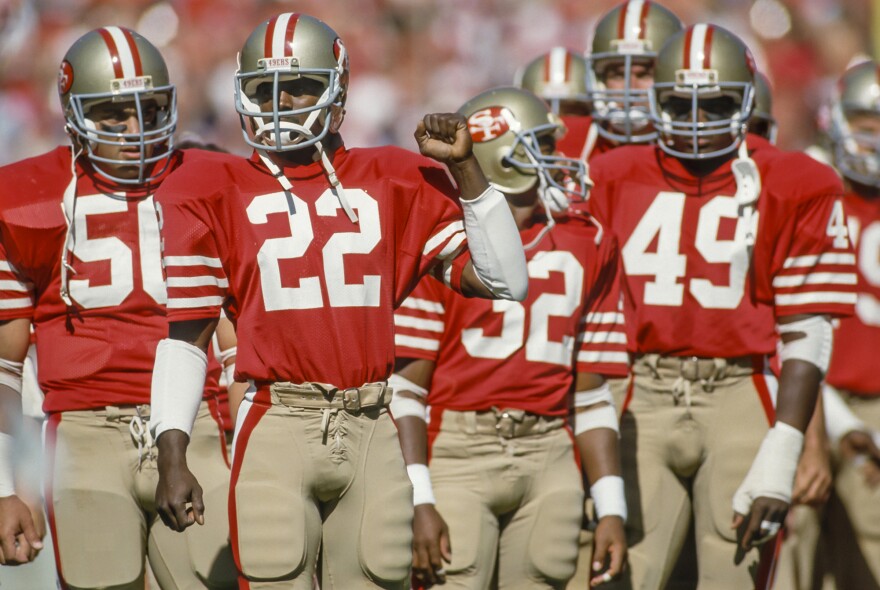

"I had a ruptured tendon in this finger. I broke my hand. Rotator cuff, shoulder injuries — but I never missed a game because of an injury," says Dwight Hicks, a former safety for the Super Bowl champion San Francisco 49ers, who plays a retired football player in X's and O's.

It wasn't until the early 2000s, Hicks says, that he realized there might be another injury he needed to worry about. That's when more and more retired players began reporting symptoms of early onset Alzheimer's. Others showed the personality changes, rage and depression that can be signs of a type of brain deterioration called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, first diagnosed in boxers in the 1960s.

"It wasn't scary," Hicks says, "until some of the prominent players — guys that I knew, some of the guys that I played against — started to have this problem."

Violence A Worry From Football's Start

Playwrights KJ Sanchez and Jenny Mercein say the growing number of affected players thrust football into an identity crisis — and not its first.

"Through every generation, we knew, we knew what the risks were," Sanchez says. There have been repeated "intense conversations about the violence of the game, the brutality of the game, and the safety of the players."

Throughout the play, there are breaks in the narrative where the cast marks some of the game's historic moments and controversies.

In 1869, Rutgers and Princeton played the first college football game. In 1905, 19 students died while playing football, spurring Harvard's president at the time, Charles Elliott, to call for an end to the sport. One academic called it "more brutalizing than prizefighting, cockfighting, or bullfighting. The rules of action are hateful. ... Football today is a boy-killing, education-prostituting, gladiatorial sport."

But Teddy Roosevelt, then president of the United States, saw things differently.

"The bruising nature of football instills manly virtues and builds strong bodies, when with each passing day America risks becoming less rugged and virile," X's and O's quotes Roosevelt as saying. "Surely we can minimize the danger without having to play the game on too ladylike a basis."

"Through every generation, we knew. We knew what the risks were."

Over the years, the protective gear players wear has improved, in an effort to make the game safer. But Sanchez says making better helmets is part of what led to the progressive brain injuries seen today.

She wrote a team physician into X's and O's to explain how recent research has shown that smaller, subconcussive hits contribute to lasting trauma.

"The brain, it's almost like a yolk inside of an eggshell," says the doctor-character (played by Marilee Talkington) as she paces the stage in a white lab coat. Even with a good helmet, "the yolk is still going to hit on one side of the shell and then the opposite side of the shell."

Are Fans Responsible?

X's and O's isn't a one-note bashing of football — Sanchez considers herself a fan.

And her co-writer, Jenny Mercein, grew up watching her father Chuck Mercein play pro ball; he was a running back for Vince Lombardi's Super Bowl champion Green Bay Packers, and also played for the Redskins, Giants and Jets.

Sanchez and Jenny Mercein say they began developing the idea for the theatrical work after a pivotal milestone in the debate about head injury: the suicide in 2012 of former San Diego Charger and 12-time Pro Bowl linebacker Junior Seau, whose brain was diagnosed after his death as showing the cumulative effects of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

The playwrights wondered whether, as fans, they had some responsibility to the players — and to the future of football itself.

"We started to talk about how many conflicted feelings we had about loving the game, now understanding the significance of the damage that the game does," Sanchez said.

X's and O's leaves it to a group of fans at a bar to work through this internal debate.

"Me and my dad watched every game together," one fan says. "And to this day, I put on a game, it's like we're back together again." Another adds: "It's like ballet. There's a beauty and a grace to it."

They ponder how long football will last if fans decide to boycott the game, or if parents stop letting their kids play out of fear of head injuries.

"If football goes away ...," another fan says, faltering. "My family, we don't go to church. We're not much for theater or concerts. Football is our way of being part of something bigger. I have to admit I'd be lonely."

The characters question recent rule changes in the game, how violent the game needs to be to be entertaining — and what they really get out of that violence.

"I think I watch it, not for the moment when the guy gets knocked down, but for the moment when he gets back up," the fan says. "I think I need to remember we can get back up."

Sanchez says she hopes to take the play to colleges and high schools. She wants to start conversations like these in the community, especially among young people who will decide whether to play or not — and how much of their future they want to bet on football.

A version of this post originally appeared in KQED's State of Health blog.

Copyright 2015 KQED