To understand China's espionage goals, U.S. officials say, just look at the ambitious aims the country set out in the plan "Made in China 2025."

By that date, China wants to be a world leader in artificial intelligence, computing power, military technology, as well as energy and transportation systems. And that's just a partial list.

"It's guidance to the rest of government and the rest of their companies and to their people, that this is what we want to be the best in class at, and therefore you should organize your activities, whether they're legal or illegal, to achieve that," John Demers, assistant attorney general for the the National Security Division at the Justice Department, said in recent testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

He said the recent legal cases against China show the country is aggressively trying to steal technology directly related to its stated goals.

"We don't begrudge them their efforts to develop technologically, but you cannot use theft as a means to develop yourself technologically, and that's what they're doing in a number of areas," said Demers.

This battle has been been going on for years and is heating up again, according to U.S. officials and analysts. It's playing out across a broad landscape that involves most every tech industry.

A different approach

This Chinese approach to espionage doesn't follow the traditional spy vs. spy battles that largely focus on acquiring government and military secrets.

China's targets cover a broad spectrum and even include things like genetically modified crops, according to Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation.

"People were stopped at U.S. airports, their luggage was examined and they had acquired seeds, seedlings, plants, literally the plants themselves," Cheng told the Senate committee.

This is just one example, he says, of why U.S. corporations, universities and research labs all need to be aware of China's broad aims.

"The Chinese see food security as part of comprehensive national power and comprehensive national security. We don't tend to think about food security. They do," he said.

The U.S.-China relationship is complex web of collaboration and competition.

Before the trade war, the Chinese were big buyers of American soybeans and other crops. Toys made in China were stacked high under American Christmas trees.

More than 300,000 Chinese students study at U.S. universities — about a third of all foreign students and far more than any other country.

Many are in cutting-edge fields like artificial intelligence, or AI, notes David Edelman, who heads a project at MIT that looks at the intersection of technology, the economy and national security.

"We have a critical gap in the United States of AI expertise," Edelman said. "Companies from Silicon Valley and elsewhere cannot hire enough trained AI experts, experts in machine learning, and foreign graduate students come to U.S. universities because they're the best."

Edelmen is well aware of the risks. He was in charge of cybersecurity at the National Security Council during President Barack Obama's administration. Yet he warns against putting up too many barriers to keep out Chinese students.

"The vast majority these graduate students that are coming to the U.S. for technical training, if they could, they would stay here," he said. "They would stay here and found a business or join a business in what is still the most thriving, open, technologically advanced innovative economy in the world and one that frankly, cannot be matched in China."

Legal investments

As China races to catch up, Chinese companies are investing openly in Silicon Valley startups. This is above board, but still raises concerns in the national security community.

"We also need to be looking at activity that is perfectly legal, but still presents a national security threat," said Demers, the Justice Department official.

The U.S. and China signed a 2015 agreement that called for an end to intellectual property theft.

Chinese hacking of U.S. companies did go down for a while, according to analysts. But it's on the rise again, and the U.S. is responding with high-profile prosecutions, even though there's no prospect that China will extradite suspects to the U.S.

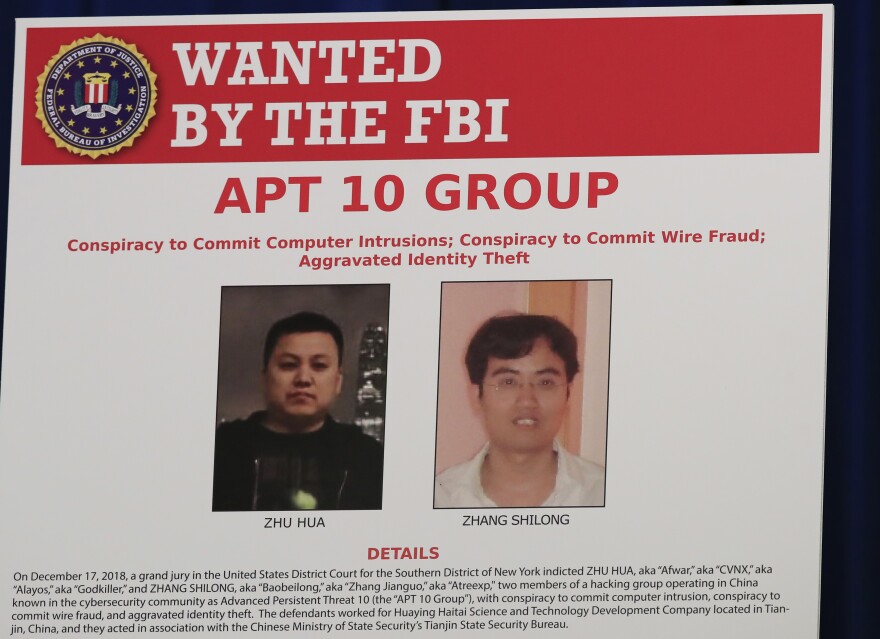

Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein held a press conference on Thursday to announce charges against two Chinese citizens who allegedly hacked their way into more than 45 U.S. tech companies as well U.S. government agencies.

Rosenstein said the private company the two men worked for was under the direction of China's main intelligence agency, the Ministry of State Security.

David Edelman expects to see more of this naming-and-shaming.

"If there's one thing that, in my personal experience, really drove some in Beijing nuts, it was the allegation that they were behind every act of cyber theft."

Greg Myre is a national security correspondent. Follow him @gregmyre1.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAyNDY5ODMwMDEyMjg3NjMzMTE1ZjE2MA001))