There is a long list of ways America was transformed by the terrorist attacks that destroyed the Twin Towers on 9/11/2001. But the question of how TV itself was changed – particularly in ways still relevant today – is more complicated.

CNBC anchor Shepard Smith, who covered the attack and its aftermath when he worked at Fox News Channel, points to a small but impactful TV innovation: the constant presence of an onscreen news ticker, scrolling through headlines, on cable news channels.

It may not sound like much today, given how so many of us now juggle multiple screens at once. But in 2001, the idea of crowding TV screens with changing bursts of information was relatively new – required by the deluge of data pouring into newsrooms regarding the deadliest terrorist attack on American soil.

"We had an information overload back then, the likes of which we never really experienced before," says Smith, now anchor of The News with Shepard Smith on CNBC. In the flood of 24/7 continuous news coverage that followed the attacks, he remembers Fox News Channel founder Roger Ailes insisting back then that the channel had to get more data in front of viewers.

"He thought that CNBC at the time did a good job of getting a lot of information on the screen," he adds. "I feel like 9/11 helped us learn to process it all."

To test some ideas about how TV was transformed by 9/11, I spoke to a range of experts, from talk show hosts to producers on fictional series. Many changes were connected to TV's reflection of Americans and the idea of America itself – notions that were challenged by a deadly attack by a terrorist group many Americans had never heard of before that day.

"Arguably, [9/11 news coverage] was one of the last examples of a common news culture, where the country was knit together by these horrendous attacks... united by a common enemy," says Andrew Heyward, who was president of CBS News during 9/11 — noting that broadcast networks shifted into cable news mode, offering continuous coverage, with no commercials, from the attack on a Tuesday through to Saturday.

Aaron Brown, who anchored CNN's 9/11 coverage that day from a rooftop, says the disaster also helped cement the idea that TV news – especially cable news channels – were expected to offer continuous coverage of major news events more often.

Brown notes, instead of spending 24 hours covering a wide range of subjects, major American cable news channels excelled when they had one big, highly emotional story to cover that the audience wouldn't dare turn away from.

"The lesson of 9/11 was that you need one great story," he adds, noting that cable news channels still tend to cover a narrow range of popular stories each day. "You feel like a schmuck if you say, [after covering a huge tragedy], 'Let me tell you about the weather.'"

Late night talk shows found voice in tragedy

These days, viewers are used to late night talk show speaking out after a momentous national events, channeling the emotions of their audience into heartfelt speeches. Comedians like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel and Trevor Noah do this pretty regularly; on everything from the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol building to the murder of George Floyd.

But that TV tradition is also a 9/11 legacy, which began when David Letterman brought his Late Show back to CBS just six days after the attacks.

"There is only one requirement for any of us and that is to be courageous," Letterman said then, admitting in that moment that he – like many viewers – might be feeling confused, angry and full of grief. "Courage, as you might know, defines all other human behavior. And I believe — because I've done a little of this myself — pretending to be courageous is just as good as the real thing."

Later, Jon Stewart would offer similar thoughts on The Daily Show, and Saturday Night Live would feature then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani giving a somber speech before a group of firefighters before executive producer Lorne Michaels asked if the show could be funny again ("Why start now?" Giuliani deadpanned.).

But Letterman had shown that his New York-based show would embody the comeback spirit of the city by returning to work as soon as possible. In the process, he set a powerful example: in the face of monumental events, hosts were now expected to address it seriously before returning to work.

And there was nothing — not even an attack that killed thousands in the city — that could keep these shows off the air for long (Tonight Show host Jimmy Fallon has said he had Letterman's 9/11 show in mind last year, when he decided to resume hosting his show from his home during the COVID lockdowns.)

"Letterman established the rule... and that had tremendous impact," said Robert Thompson, founding director of the Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University. "It's like, if your dad never cries, then when he cries, you pay attention."

Fictional shows react to American frustration, anger

On the other side of the country, hours after the attack, the creator of NBC's hit political drama The West Wing began planning how to explore the issues raised by Al-Qaeda's attack.

The result was a landmark episode called "Isaac and Ishmael," written by creator Aaron Sorkin that aired on NBC three weeks after 9/11. The story toggles between two scenarios: most of the characters talk through terrorism issues with a group of high school students briefly confined in the White House during an emergency drill, while the Chief of Staff unfairly grills a Muslim staffer who had the same name as an alias used by a wanted terrorist.

The episode itself was occasionally clunky and preachy. But Kevin Falls, a co-executive producer on The West Wing at the time, said the attacks had changed the world's attitude about foreign policy and terrorism so much, the show had to acknowledge what happened, even obliquely.

"What Aaron was doing was important because we were all united and very angry about what happened and probably thirsting for some revenge," Falls says. "So he actually tapped the brakes and said 'Hey, remember to put a face on this and not include all Muslim Americans with a broad brush.'"

Now Falls serves as a co-executive producer on NBC's hit family drama This Is Us, which faced a similar challenge last year as the show decided to include storylines addressing real world events like the pandemic and the impact of George Floyd's killing. One of the show's characters, a veteran of Afghanistan, is a reminder of 9/11's legacy, allowing the series to ask deeper questions about the damage resulting from long, punishing American military operations in distant parts of the world.

"The Vietnam vets felt betrayed by their country; the Afghan war vets, a lot of them feel that they've betrayed the people in Afghanistan," Falls adds. "Our show wears its emotions on its sleeves... we can't ignore that."

"24" and "Homeland": shows shaped by 9/11's legacy

Executive producer Howard Gordon worked on two fictional shows that have come to symbolize how 9/11 affected and inspired TV storytelling: Fox's 24 and Showtime's Homeland.

On 24, which debuted just a few months after 9/11, Kiefer Sutherland's stalwart government agent, Jack Bauer, would do whatever it takes to stop a bad thing from happening. Gordon says, particularly after the show's first season, Bauer became a proxy for America's post-9/11 anger at terrorists and any incompetent or corrupt government officials who made it tougher to stop them.

But over the years, producers heard from advocates for Muslims and military officials who said storylines featuring a Muslim family in America as a secret terrorist cell and scenes of Bauer effectively using torture to extract information were encouraging prejudices and misinforming viewers.

The concern: That a focus on American and Christian perspectives was leading to damaging story choices.

Gordon says he was surprised to see reaction to 9/11 and wars overseas turn his kinetic action thriller into "this crucible for these very, very radioactive and challenging, soul-searching ideas... (It) really forced me, and I think all of us, to do a gut check."

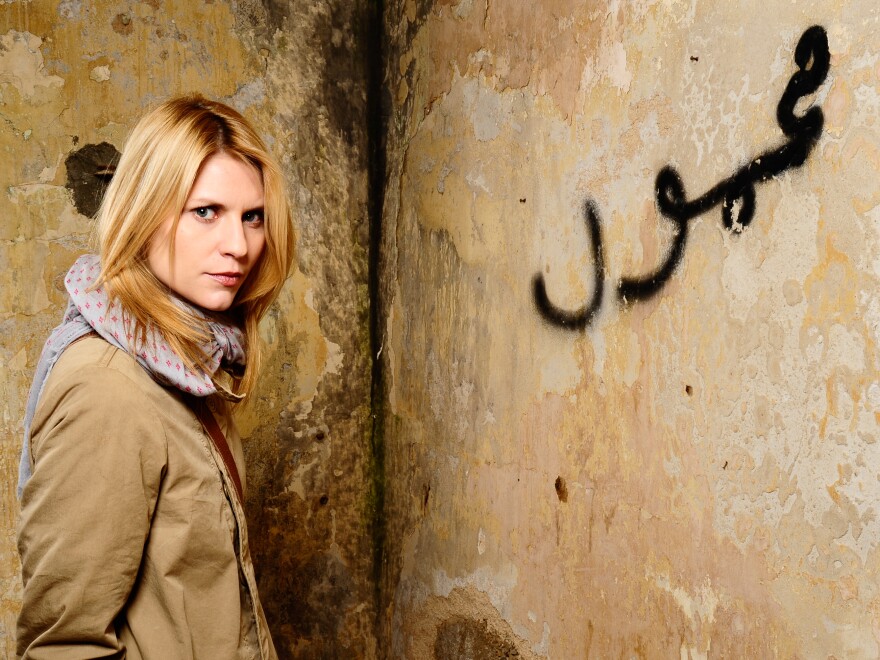

Such issues surfaced again on Homeland, the Showtime series Gordon began working on soon after he finished 24's original run on Fox. Teaming with longtime colleague Alex Gansa, he adapted an Israeli TV drama called Prisoners of War into the series — focused on an American soldier returned to the U.S. after he was held captive by al-Qaeda, and his connection to a female CIA officer who suspects he has been brainwashed.

Gordon says the series allowed him to more deeply explore themes hinted at in 24. Still, the show was also criticized for an Americanized point of view that led to problematic portrayals of Muslims and countries in the Middle East, including an incident where graffiti artists hired to decorate one of the show's sets wrote messages in Arabic accusing the program of racism.

"It was a sobering moment," says Gordon, who adds the show worked harder to avoid stereotypical depictions of Muslims after that incident. "As careful and inclusive as we tried to be, we still failed. And even now, we're still asking ourselves what happened [in Afghanistan]... was it folly? What's America's place in the world? I think I'm as confused now as I was back then."

Dissenting voices struggled for visibility

Phil Donahue says reluctance among some TV networks to question the war in Iraq after 9/11 helped end his TV career.

Donahue, already a TV legend for creating and hosting his long-running self-named daytime talk show, began hosting a talk show on MSNBC in 2002. He had hoped to make the program a showcase for his skepticism about the Iraq war, but found the cable channel reluctant to challenge the Bush administration's drive toward conflict.

"I thought I was going to be a hit because I was different," says Donahue, now age 85. "Everybody else was beating the war drums, and I wanted to get on the air and say 'Why are you doing this?' But it was clear, after awhile, they wanted aggressive people who were patriotic and any kind of head-scratching that we tried to do just wasn't welcome."

Back then, MSNBC had different ownership and executives; it hadn't yet developed a lineup of liberal-oriented pundits (full disclosure: I occasionally appear on the channel as a media analyst). TV news anchors across the dial were facing pressure to wear American flag pins on their lapels and talk show host Bill Maher saw his show Politically Incorrect canceled by ABC in 2002, after he sparked controversy by saying not long after 9/11 that the plane hijackers were not cowards.

In 2003, referencing disappointment with his ratings, MSNBC canceled Donahue's show after less than a year on air. But Donahue is convinced public pressure to support a president who said he was fighting back against terrorists helped do him in. "The reporting of bad news is more important than the good news," Donahue says. "But for a long time, it was very hard to make that point. The jingoism has really created a roadblock to truth."

CNBC's Shepard Smith, who left Fox News in 2019 amid disagreements with hosts from some of the channel's opinion shows, says he remembers being handed a flag pin to wear on air after 9/11 and seeing the channel after 9/11 become more jingoistic, with images of the American flag onscreen.

Smith says he tried to focus on traditional reporting and staying measured to reassure viewers.

"The last thing you want to do is unnecessarily add more angst and heartache, fear or division," he adds. "The way you present information matters a lot when things are at their most extreme, the most dramatic... When s---'s hitting the fan, you've got to be the voice of calm."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.