When Suncoast Searchlight first revealed how real estate developers were using special-purpose governments to shift the cost of building new local communities onto future homeowners — while keeping control over how the money was spent — elected officials downplayed the risks.

“Buyer beware,” state lawmakers and county commissioners told reporters.

No one was forcing people to move into these neighborhoods, where developer-run boards can impose long-term tax burdens with little resident oversight. If homeowners didn’t like the arrangement, officials argued, they could simply buy elsewhere.

But a first-of-its-kind analysis by Suncoast Searchlight reveals that buyers increasingly have little choice.

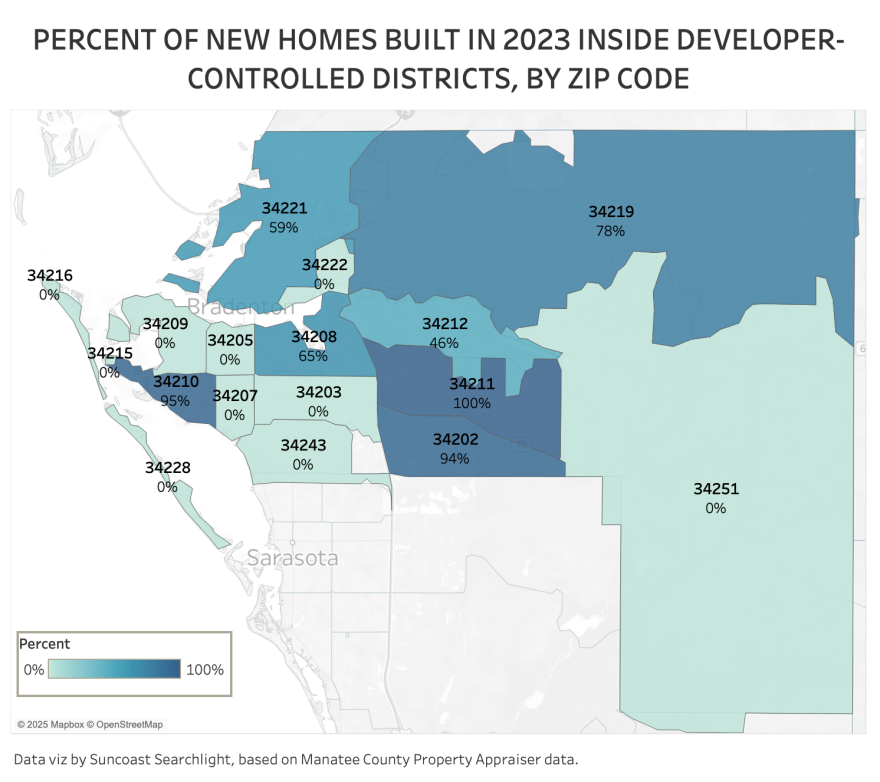

Nearly 3 out of every 5 new single-family homes and condos built in Sarasota and Manatee counties were located within special taxing districts governed by developers in 2023, the latest full year for which data was available. That’s up from less than 1% in the early 1990s — a sign of the control developers now wield over tens of thousands of residents along Florida’s Suncoast.

In Manatee County, the region’s biggest driver of recent growth, more than three-quarters of all single-family homes and condos built in 2023 were within a developer-controlled district.

For three of Manatee’s ZIP codes, where more than 65,000 people now live, more than 90% of the new homes and condos to come out of the ground that year were inside such a district.

“You can go an entire area — entire ZIP codes — in states like Florida and Texas, where nearly every home is in one of these,” said Patrick Johansen, founder of the volunteer-based HOA Reform Leaders National Group. “These are governments in the U.S. that don’t run like any other governments in the U.S. They can raise fees, take that money and spend it almost any way they want.”

Reporters reviewed hundreds of thousands of tax collector assessments and property appraiser records in Sarasota and Manatee counties to determine how much new construction now falls under these quasi-governmental entities, including the more commonly-known community development districts, or CDDs.

These districts are fueling the fastest-growing communities in the region, allowing developers to issue tax-free, municipal bonds to finance construction, while passing long-term costs to homeowners, often at a scale that dwarfs their property taxes. The special assessments often add thousands of dollars to annual homeowner tax bills for decades.

Homeowners last year paid anywhere from about $500 at Heritage Harbour South in East Manatee County to more than $6,300 in total district fees for certain phases of Lakewood Ranch. That’s often on top of separate neighborhood HOA dues, a Suncoast Searchlight investigation found.

With little oversight and no resident input, developers can maintain control over spending decisions and district governance for decades.

An ongoing Suncoast Searchlight investigation revealed developer-led governments in the region have floated nearly $10 billion in municipal bonds between Sarasota, Manatee and DeSoto counties — nearly a third of them authorized during the past five years.

ALSO READ: Power and profit: Developers gained government status, then got bonds to build big

Coldwell Banker agent Tom Palazzo said few, if any, of his clients are deterred by the prospect of living in a CDD. Many are cash buyers from the Northeast, where property taxes are higher, and they view the additional fees as a fair tradeoff for the perks CDDs provide — like pools, parks and pristine landscaping.

But he worries about younger or first-time homebuyers trying to break into the market.

“For a lot of people, especially those financing their purchase, it can be difficult — like, ‘I have a house payment and an HOA payment and now CDD payment, too?’” he said. “It’s a tough pill to swallow.”

Special districts date back to the early 1980s. For decades, they were used to beautify luxury neighborhoods that wanted more amenities — sidewalks, parks, street-lighting and other enhancements — than local governments could provide.

Now, it’s becoming the only option for new homebuyers in a growing segment of the Suncoast.

Even after a wave of defaults during the Great Recession, the model has gained steam. As available land shrinks, developer-governed communities are becoming not just common, but nearly unavoidable for buyers looking to build a new home on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

“The future property owners are really the ones that bear the burden,” said Terry Henley, a lecturer at the University of Central Florida’s School of Public Administration, who’s published research on special purpose governments. “It can be a lot more expensive to live in one of these districts.”

“If you’re going to have this many CDDs, you need more oversight,” he said. “The optics are that the fox is guarding the hen house.”

Manatee County sees explosive growth inside developer-run districts

Drive east from Bradenton toward the interior of Manatee County, and the transformation is impossible to miss.

What was once a patchwork of cattle ranches, quiet farmland and open wilderness has given way to rows of rooftops, winding cul-de-sacs and manicured entrances. Master-planned communities now dominate the landscape, built fast and financed through special-purpose governments controlled for years not by residents, but by the developers who created them.

At the height of the region’s recent housing boom in 2023, more than 5,000 new homes and condos in Manatee County were built inside special development districts.

Nowhere is this shift more dramatic, or more concentrated, than in Parrish, Lakewood Ranch and portions of West Bradenton.

Lakewood Ranch, a 35,000-acre master-planned development that spans the Sarasota-Manatee line, functions almost like a city — with a bustling main street, parks, golf courses and a growing network of residential neighborhoods. Built through a web of special taxing districts starting in the 1990s, it has become a statewide model for large-scale suburban development, where infrastructure is financed by municipal bonds controlled by the developers.

While construction began decades ago, growth hasn’t slowed. New communities like The Isles, Windward and Shellstone continue to push east and north — all within special districts.

Two ZIP codes that cover parts of Lakewood Ranch — 34211 and 34202 — have become ground zero for this expansion. Together, they stretch from University Parkway north to State Road 64 and from Interstate 75 east to Bourneside Boulevard and beyond. Nearly every new home built in these areas falls within a special district, backed by bond debt that homeowners must repay through annual assessments.

The Lakewood Ranch Stewardship District was authorized to float $4 billion in municipal bonds in 2005 and another $50 million in 2022. That helped Lakewood Ranch become one of the fastest-growing communities in Florida, a massive residential and commercial development rivaling The Villages retirement mecca near Ocala.

Lakewood Ranch master developer Schroeder-Manatee Ranch CEO Rex Jensen did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Similar patterns are now unfolding in Parrish, an unincorporated area in northeastern Manatee County. With no municipal government of its own, Parrish has attracted developers eager to build through special districts, which allow them to finance roads, utilities and amenities without traditional oversight.

Nearly 4 in 5 homes built in 2023 in Parrish were located in a special governing district, according to Suncoast Searchlight’s analysis.

Pastures and pine flatwoods are giving way to sprawling new developments there, like North River Ranch, which markets itself as “a new hometown” with a massive clubhouse, resort-style swimming pool and playground; and Prosperity Lakes, an “amenity-rich lifestyle” neighborhood for adults 55 and older.

“What it’s become is the only way to get new communities developed anymore, because local governments simply aren’t going to finance those types of public facilities because they don’t have the money to do it,” said Chris Jones, an economist at the University of South Florida.

West Bradenton joins the boom as concerns emerge over growth model

It’s not just inland areas like Parrish and Lakewood Ranch where special districts have taken root. On the west side of Bradenton, new development has surged in areas once home to flower farms and protected wetlands.

One such project is SeaFlower, a sprawling community rising on more than 1,000 acres near the Sarasota Bay. Backed by $373.7 million in bonds issued through a special district — the Lake Flores Community Development District — it’s slated to include 4,000 residential units, a hotel, grocery store and other retail space.

Nearby, the Aqua by the Bay development is taking shape on another 500 acres through its own district, with plans for thousands of homes and apartments — and a 4-acre artificial lagoon as a centerpiece.

Medallion Home began building Aqua in 2020 after more than a decade of permitting and legal battles tied to protected mangroves, prompting the Manatee County Commission last year to roll back certain wetland protections for the project.

Medallion Home CEO Carlos Beruff did not respond to calls and text messages seeking comment for this story.

In Sarasota County, a smaller share of new homes and condos fall within these districts. About 2,100 new homes in Sarasota County sprouted up within CDDs in 2023 — less than half of what was built in Manatee County.

Manatee County Commissioner George Kruse said the pattern of developers pushing further east on vacant pastures – and using CDD bonds to build the infrastructure — is “easy” and “lazy.” He says he’s trying to encourage more infill development in areas where there’s already established roads and sewers.

But he also does not believe Manatee County has approved too many new CDDs in recent years, citing codes that allow it. He also said he doesn’t believe it’s the county’s job to make hyper-local decisions that these special district boards do, like rules about street parking or whether a neighborhood playground needs replacing.

Without these types of new developments, Kruse argues the droves of cash-rich northerners who continue to move here will displace existing residents, creating a supply/demand imbalance and skyrocketing home prices.

“This infrastructure has to be built somehow, so I guess the question is who’s going to pay?” said Kruse, who lives in a CDD himself. “At the end of the day, it’s a glorified HOA. They want to assess (residents) to repave a road? Good. I don’t want to repave the road, and someone needs to do it.”

Officials downplay concerns as buyers shoulder the burden

Every special district in Florida must be established through a local ordinance — at city hall or the county commission — or by a specific state law in the Florida Legislature setting the district’s authority.

After Suncoast Searchlight published “Power and Profit” in May, elected officials contended they had not approved too many new districts in recent years.

State Sen. Joe Gruters, R-Sarasota, told Suncoast Searchlight in May these special districts “have their purpose. The question is do buyers want to live there or not.”

County commissioners in both Manatee and Sarasota cited some concerns about the growth of CDDs, but stopped short of agreeing to any moratoriums or regulations to slow the pace.

But experts who spoke with Suncoast Searchlight were alarmed to learn of the current CDD ratios in the local real estate market.

Without reform, they fear consumer options will only get worse, shoehorning buyers who can’t afford the assessments into CDDs because there is nowhere else to live.

District assessments and financing are “foreign to everybody not deeply involved,” said Bruce Barnes, an attorney representing homeowners in a Clearwater CDD organized by two men convicted of running a Ponzi scheme. The CDD was not part of the Suncoast Searchlight analysis for this story. “The victims are the owners who are saddled with bad debt assessments. It’s ripe for abuse.”

Some also question how homebuyers could possibly factor in the worst-case scenario if the economy sinks. Should any of these districts default on their bonds, homeowners must continue paying CDD assessments — getting no maintenance in return — or risk losing their homes.

Eleanor Wilking, an associate professor of law at Cornell, said she’d be “shocked” if homebuyers factor that risk into their financial calculations. Most wouldn’t be able to, she said.

“These are not a perfect substitute for local government — they are not even a close substitute.”

Kara Newhouse is an investigative data reporter, Josh Salman is a senior investigative reporter/deputy editor and Derek Gilliam is an investigative watchdog reporter for Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.

This story was originally published by Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom delivering investigative journalism to Sarasota, Manatee, and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.