Editor's note: This book review deals with themes that may be distrubing to some readers.

It's no secret that many of us find cult narratives fascinating. They're full of interesting characters, dramatic arcs and, often, salacious, shocking details.

But the paramount questions we seem to want answered are: How did you get in? and How did you get out?

There's no shortage of books answering these questions when it comes to the infamous Children of God — or The Family International, as it is now called.

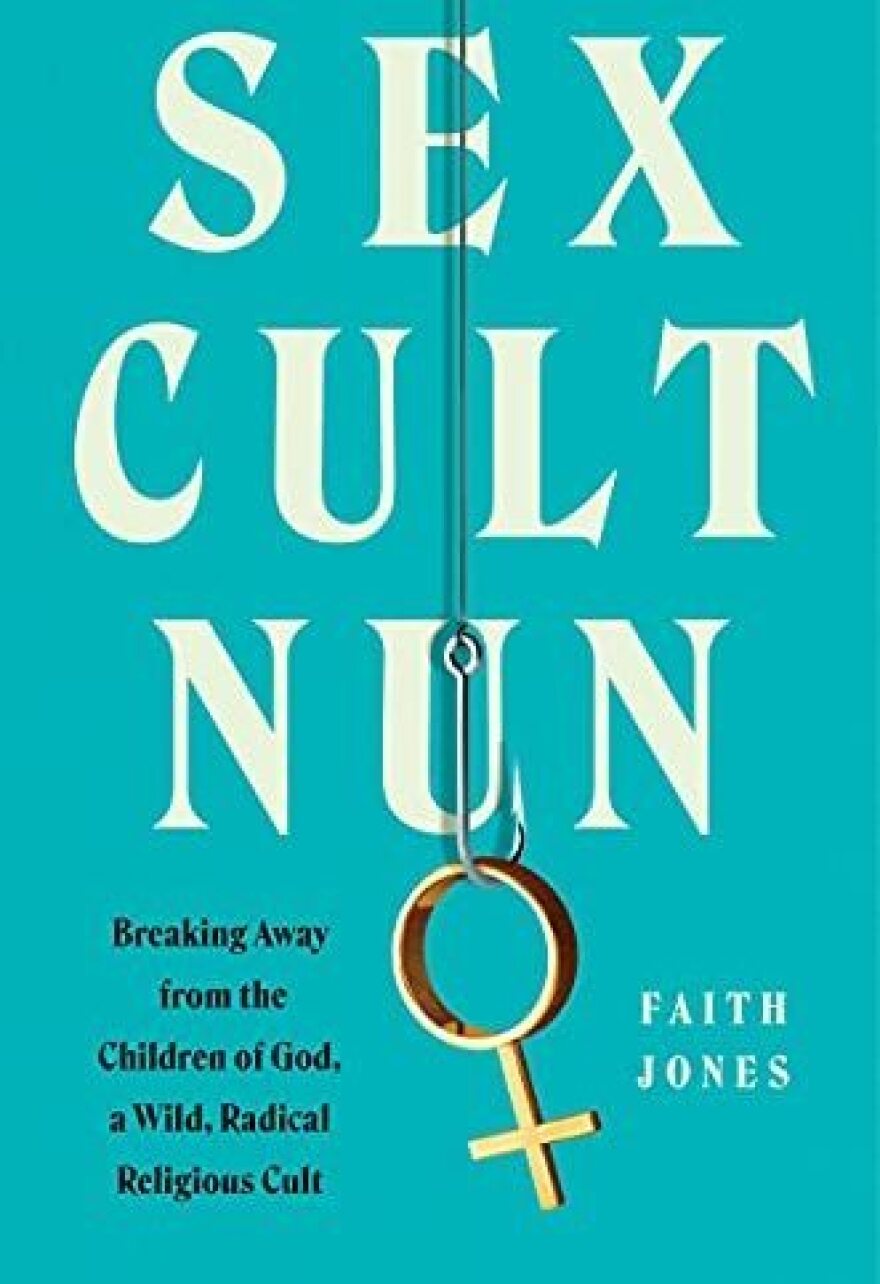

The latest, Sex Cult Nun: Breaking Away from the Children of God, a Wild, Radical Religious Cult, is written by Faith Jones, a successful lawyer. She's a granddaughter of David Berg, the founder of The Family, and was raised in the cult from infancy — among many siblings born to her father and his two wives — until managing to leave it for good in her early 20s.

Jones was one the group's second-generation members — or SGMs, in cult lingo — now old enough to have achieved enough distance from her traumatic upbringing to begin talking about it publicly. Others have done the same in past few years — Flor Edwards with Apocalypse Child: A Life in End Times; the upcoming Rebel: The extraordinary story of a childhood in the 'Children of God' cult by Faith Morgan; Cult Following: My escape and return to the Children of God by Bexy Cameron (not yet available in the U.S.); and Lauren Hough's Leaving Isn't the Hardest Thing, which, as I wrote in my review, is about a lot more than the cult experience itself.

That so many books about a single cult exist seems to demonstrate just how widespread and large it was, as well as the appetite readers have for new information about The Family.

Jones opens her book with a history of the cult and its phases, giving unfamiliar readers a helpful overview. The majority of the memoir recounts her childhood and teenage years, starting with her nuclear family moving to Hac Sa, a village in a remote part of the island territory of Macau, off the south coast of China. There, her siblings, her father, and her two mothers slowly won over the locals by cleaning up the streets and putting pressure on their contacts in Macau to begin providing electricity and plumbing to the area, which had not been receiving many basic municipal services. Other members of the Children of God would come through, some staying briefly, others for years. Over time, what was at first a collection of dank and abandoned buildings became a bustling little commune.

Jones writes about these years as if still within the perspective of her child self, with relatively few asides noting how disturbing aspects of her life are. For instance, she matter-of-factly explains: "Since we are all 'family,' any adult can spank any kid... Grandpa says 'OUR CHILDREN BELONG TO THE FAMILY and all of us, and we are all their parents and they are all our children.'" Movingly, she also admits that as a young child she's resentful of the fact that all the kids are supposed to refer to Berg, or Moses David, as "Grandpa" because he's her real grandpa but not theirs, even though she's never met him. "But that would get me a smack and a lecture on how he is all our grandpa in spirit."

Sex pervades Jones's life from a young age. As she writes, the Children of God used sex for many years as a recruiting and fundraising tool, as well as a form of control. She notes that women were required to "share" — have sex with — the men they lived with, regardless of their relationship status or attraction. To not make oneself available to such contact, she writes, implied that a member of The Family was not committed enough to God and to Moses David, their leader, and there were harsh punishments for such unwillingness to yield.

Jones witnesses her mother sleeping with men she's reviled by, and is pressured into sexual contact with adult men when she herself is a child. As she grows up and the unwanted sexual coercion mounts, Jones wrestles with how uncomfortable she feels about it all. Yet this is all she knows, having been largely cut off from "the System" — the world outside the cult and its members — her whole life. She continually convinces herself that she's working for the glory of God, to try to save as many people from the disastrous End Times to come, and her disillusionment comes slowly, bit by bit. It takes years for her to fully leave, and her journey out is an often painful one filled with horrors, delusions, traumas, triumphs, moments of tenderness, and the occasional actual humanitarian work alongside all the proselytizing.

Where the book begins to falter and become occasionally aggravating is when Jones begins her life in the United States in her early 20s, having officially and intentionally left The Family in order to do so. Having discovered the wonders of books and the power of education during a brief stint in the U.S. as a teenager, Jones is eager for traditional schooling after her years of learning on her own. She quickly makes a connection that the way to education ends up being rather similar to her indoctrination in The Family: "They give you the answers, you learn them, and then they grade you on how well you can recite them with a slightly different flavor." Fair enough: Yet, despite being astute about some aspects of the "System," she seems to forget the very real systems that exist within it.

Throughout her childhood, she uses Winston Churchill's maxim, Never give in, never, never, never, to help her bear the hard moments, and develops a grit-your-teeth-and-bear-it mentality. This is entirely understandable, since she lived in a world where any deviation from the rules — rules which changed often enough to keep everyone off-balance — could result in physical and emotional abuse. Yet she's translated her approach to personal survival into a message she seems to think everyone could benefit from, a bootstrap message of personal responsibility above all.

Stranger still is Jones' revelation toward the end of the book in which she describes her approach to life and women's liberation as being similar to American property laws. She views each person's body as property that they alone have an inalienable right to — yet then celebrates the men who wrote "right to Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness," many of whom believed they absolutely had the right to own other people. (She admits, understating, that they "messed up by not applying it to all humans.")

It's also rather uncomfortable, talking about indoctrination, to witness Jones trying to sell her TEDx Talk message at the end of the book, especially when she applies it so broadly as to sound, suspiciously, guru-like: "I've crystalized our fundamental moral philosophy, the DNA of our legal system, morality, and human rights into a single simple diagram that I can teach to a curious eight-year-old." The book might have had more impact if Jones had shared her story without trying to tack on a single, overarching, packageable message at its end.

Ilana Masad is an Israeli-American fiction writer, critic, and founder/host of the podcast The Other Stories. Her debut novel is All My Mother's Lovers.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.