SPECIAL REPORT: The pressing water issues facing north central Florida

Three miles west of High Springs flows a sanctuary of shimmering water surrounded by sun-kissed trees. Turtles sun themselves on the banks, children splash around on the steps descending into the cool water and warm breezes rustle the treetops and the feathers of white ibis.

Poe Springs is the largest spring in Alachua County, and a beloved spot for kayaking, swimming and other water fun. Locals and visitors from afar drive down the dusty back roads and make the 0.3-mile hike down to the isolated spring to enjoy the year-round 72 degree flowing waters.

However, these once-pristine waters are now green, as algae continues to take over the bed of the spring, and their gushing flow has slowed over time.

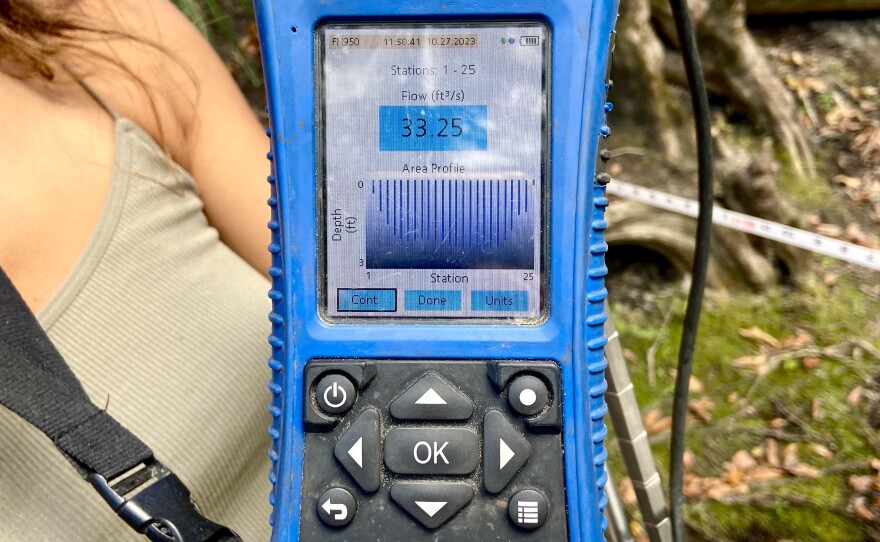

Scientists measure the freshwater springs for flow, that is, the quantity of water that bubbles up from the aquifer into each spring daily. On October 27, 2023, the Florida Springs Institute (FSI) measured the flow of Poe Springs.

The measure multiplies area by velocity, explains FSI aquatic ecologist William “Bill” Hawthorne as he stands knee-deep in Poe. Hawthorne and two FSI interns, Katrina Koning and TJ Comer, pulled a tape measure across the length of the spring. Then, they used their portable flow meter–a tall metal pole that measures the water’s height–connected to a handheld digital screen that calculates velocity.

The calculation shows scientists flow in cubic feet per second, or CSF. Historically, Poe Springs flowed at about 60 CSF, or nearly 39 million gallons of water per day. According to Hawthorne, a healthy range consists of plus or minus 5 CSF from this historical average. If the CSF were a negative number, it means the direction of water has reversed–the spring’s water has actually begun to flow back into the aquifer.

On that warm October day, the scientists found that Poe Springs was flowing at 33.25 CSF, or nearly half the expected average. This equates to 21.49 million gallons of water flowing out of the aquifer and into the spring each day.

As Poe Springs continues to deteriorate in quantity of water, other springs in Florida are facing similar outcomes.

Known for its sparkling, blue springs and gator-filled lakes, Florida is home to a network of waterways that play a crucial role in sustaining the state's rich biodiversity. Among these water sources are over 1,000 springs, with crystal clear waters, vibrant plant life and a diverse array of aquatic species, such as mullet and sunfish.The Floridan Aquifer, the largest aquifer in the southeastern United States, provides drinking water to 90 percent of Floridians and is the primary source of freshwater for the springs delivering a continuous flow of fresh, cool water.

However, as more people move to North Florida, more wells are dug, more tourists visit for recreation and farmers irrigate more crops, these beloved springs and our aquifer face overuse. Between overpumping and pollution from fertilizers and septic tanks, natural waterscapes reflect how we treat them.

Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson is one of several environmental activists in the region who work to protect local freshwaters. Jipson is the owner of Rum 138, a kayak and canoe rental service on the Santa Fe River. She is also a director and previous president of Our Santa Fe River, a non-profit that advocates for protecting the aquifer, springs and rivers in the local watershed.

“This river isn’t going to be here if we keep using it the way we are using it,” Jipson said. “We are overusing our water resources, not only by extraction from our own tap at home or at business, but also through recreational use, people trashing the river, or people stomping around on the vegetation.”

Jipson said people complain that they can no longer tube the sensitive, shallow northern section of the Ichetucknee River. But the river and its springs, along with others such as Blue Springs, need these limitations on recreational use to heal.

“The more we interact with the bottom of the riverbed, the less habitat we have for nature,” Jipson said. “Our drinking water and our spring water are the same, so we need to do everything we can to protect them both.”

Robert Knight, founder of the Florida Springs Institute, compared the state of natural waters to a balloon and pins.

“The balloon is the aquifer full of water and when you start putting a million little wells in it, that’s a lot of air coming out of the balloon, which is a lot of water coming out of the aquifer,” Knight said. “The aquifer is in trouble.”

Some of that trouble was visible July 15, 2023, in Blue Springs, when an underground collapse caused the flow to stop and the water to turn brown and murky.

“We create cavities when we are moving water from one particular area continuously for days on end,” Jipson said, “and water will then migrate and the pressure system underground will change.”

While the water at Blue Springs eventually cleared up and the flow began again, such collapses could continue amid more intense water withdrawals, Jipson said.

Flow is not the only impact of groundwater pumping. The intense withdrawals can also harm water quality.

Stacie Greco, Water Resources Program Manager at the Alachua County Environmental Protection Department, said that nitrogen and phosphorus are another problem facing springs.

“The top water quality threats are nutrients,” Greco said.

According to a report by the Florida Springs Institute, over 80 percent of Florida’s springs are polluted by nitrates. Meanwhile, the Santa Fe River’s nitrogen pollutant levels increase by roughly 1,900 tons each year.

The water at Poe Springs currently coexists with algae, facing a constant battle for space within the spring and for the nutrients and oxygen that plants and animals need to survive. The bright green algae are primarily caused by tannins in the water, which derive from nitrates and groundwater pumping. According to Hawthorne, the nitrates that are found in the water are from fertilizer runoff from nearby farmland and personal landscaping.

Knight warned that the state of the Floridan Aquifer is worse than it has been in years prior. Floridians need to understand the importance of this underground resource and how their habits have increased these nitrates in the water, he said.

“We are tapping it for all of our uses; not just for drinking water, but for watering our lawns and watering our crops, and every one of those uses actually contributes to nitrogen pollution to the aquifer,” Knight said. “Our aquifer is highly polluted with nitrogen, which is highly toxic to our springs and highly toxic to humans. It’s not a pretty picture for future generations.”

However, in the FSI report, Knight explains that all hope is not lost. By limiting fertilizer use and changing wastewater management practices, nitrate levels can be stabilized, and these freshwater springs and rivers can be restored over time.

SPECIAL REPORT: The pressing water issues facing north central Florida

Copyright 2024 WUFT 89.1