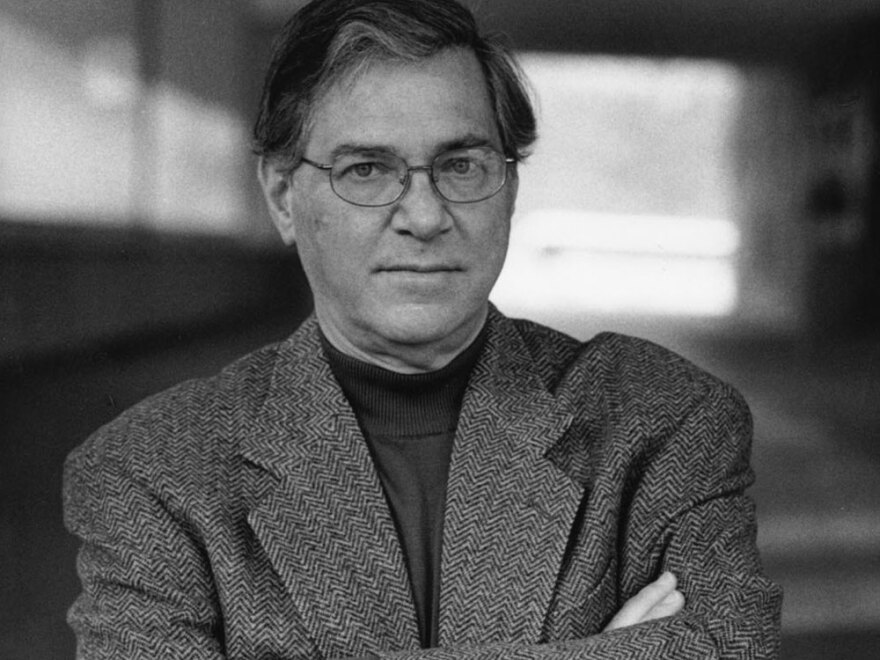

Journalist Michael Klare says the age of "easy oil" is over.

"Easy oil would be the stuff that would be easy to get out of the Earth, in large reservoirs, close to the surface or in shallow, coastal areas, or in friendly countries that are law-abiding and nearby," he tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross. "All of that oil is now gone. We'll never see it again."

Klare has written several books about the oil industry. Blood and Oil examined America's dependence on foreign sources, and his latest, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet, focuses on the geopolitical problems countries face if they don't find alternative energy resources.

He sees America entering a new era: one of "tough oil."

"Tough oil is deep underground, far offshore, in complex geological formations like shale rock or in the Arctic. Or in unfriendly, dangerous countries," he explains. "That's what I mean by tough oil. That's all that's left on the planet, so that, to the degree to which we remain dependent on oil, that's what we're going to have to go after."

But going after the "tough oil," Klare says, is tough in part because of the complexities of weather, geology and politics. And he warns that deep-water drilling in "tough oil" areas may well lead to more disasters like that of the Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico.

"I think that when you engage in drilling in environmentally hazardous areas -- which is the trajectory we're on -- more such disasters are inevitable because we're operating in places increasingly where the geological formations are unfamiliar, unknown -- and where the Earth will behave in unexpected, unforeseen ways, and we can't protect against all of these unforeseen events. So all kinds of disasters are likely to occur."

Interview Highlights

On the Deepwater Horizon disaster

"We have been drilling in the Gulf of Mexico for a very long time -- at least 40 years. Almost all of the wells in the Gulf of Mexico are very close to shore in shallow water -- 100 feet, a few hundred feet. But virtually all of that oil close to shore has now been exhausted. So anything left in the Gulf of Mexico is going to be in very deep water, as much as a mile of water -- which is what the Deepwater Horizon was drilling in -- even deeper than that, and then going much further underground. So we're drilling under very difficult and hazardous conditions in many cases. The water pressures are enormous at that level. Humans can't operate down there. You have to rely on robots. And the Earth can behave in unusual and unpredictable ways."

On the danger of hurricanes

"The hurricanes produce high winds and big waves, and these can topple the oil rigs that are out there in the deep water, they can damage the facilities, and they make it impossible to operate -- so you have to evacuate the crew. Now the big danger is that it will snap an underground facility -- the pipes, the risers -- and spill oil into the Gulf. Of course, the oil companies say there's no danger of that because of the blowout preventers and other safety devices that are supposed to shut off the flow of oil in the event of a hurricane. But we now know we can't count on those devices to shut off the flow of oil in an emergency."

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.