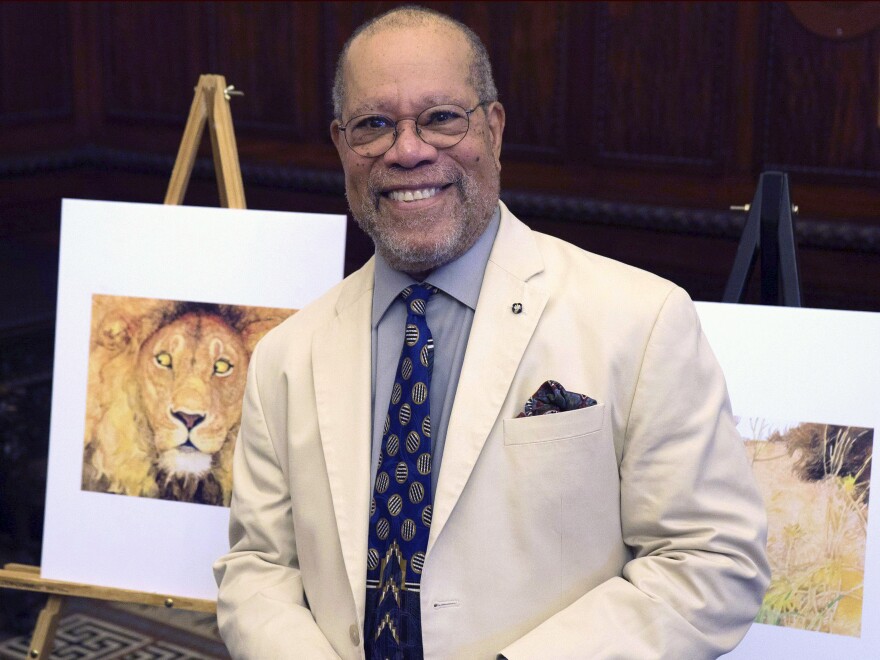

The celebrated illustrator Jerry Pinkney has died. According to his long-time agent Sheldon Fogelman, Pinkney suffered a heart attack today; he was 81.

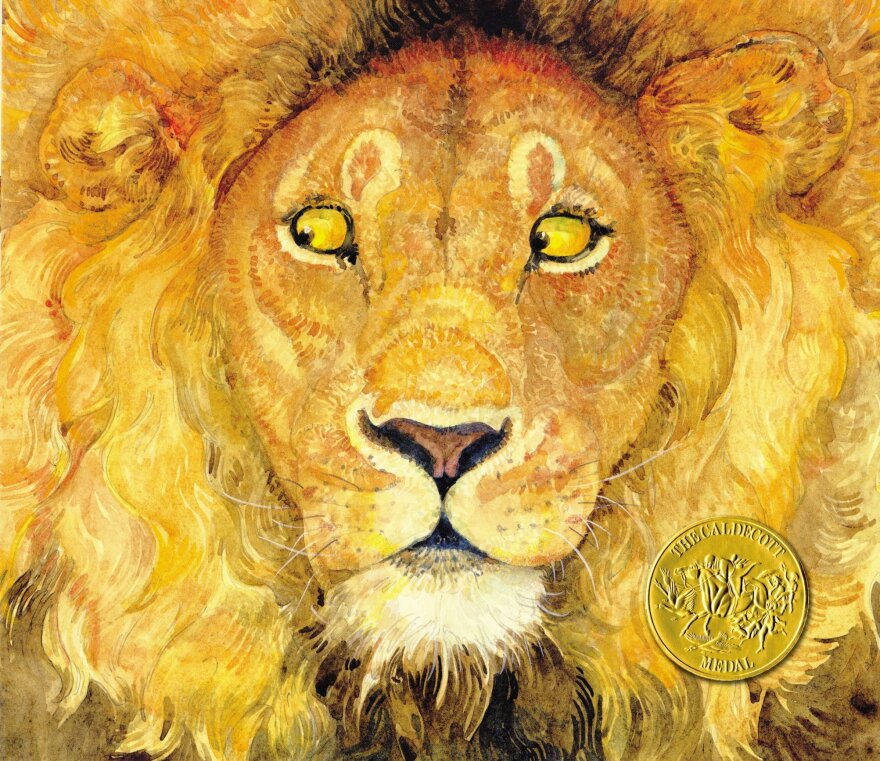

Pinkney was a legend in the world of children's publishing. He won a Caldecott medal for his 2010 picture book The Lion and The Mouse; he also won five Coretta Scott King awards from the American Library Association and a lifetime achievement award from the Society of Illustrators. Over the course of a nearly six-decade long career, he left his mark on over a hundred books, mostly for kids and teenagers, beginning with The Adventures of Spider: West African Folk Tales in 1964.

Gen X readers will remember Pinkney's covers for Virginia Hamilton's The Planet of Junior Brown from 1971 and Mildred D. Taylor's novel Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry in 1977. And millennials will remember the numerous books by Julius Lester that he illustrated, including John Henry and The Last Tales of Uncle Remus. Pinkney also frequently collaborated with his wife, Gloria Jean, a children's book author.

"I was born in 1939, smack in the middle of a family of eight. Growing up in the 1940s, I was also smack in the middle of another turbulent era in American history. Our country was still recovering from the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression was finally ending, and World War II was just beginning," Pinkney wrote in a 2016 essay for WHYY — which you can find here. "In the 1940s, Philly was not as plainly segregated as many of the Southern states, but there was still often an implied separation of the races — limitations on where we could go, things we could do, who we could talk to. Stores did not have any 'whites only' signs posted, but the 'open' sign on the door didn't always mean that my friends and I really could enter and be served. I never knew if that 'welcome' sign included my parents, uncles, aunts, and the black adults who were our neighbors, teachers, and pastors — those very individuals who tried their best to instill a sense of self worth in us."

Making art, Pinkney said, was how he espcaped this hard reality. He earned money to buy art supplies by shining shoes while sharing a house with five siblings in a six-room, two story house in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. Drawing, he said, was where he felt safe.

Pinkney was also known as a mentor to other artists such as James Ransome, and Brian Pinkney, his son, who is now a children's book illustrator himself.

"I am a storyteller at heart," Pinkney told the Society of Illustrators. "There is something special about knowing that your stories can alter the way people see the world, and their place within it."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.