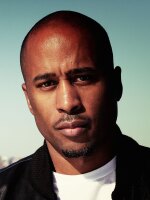

Andre 3000 — née André Benjamin, sometimes Three Stacks and always one half of the mighty OutKast — sat down with Microphone Check hosts Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Frannie Kelley before a screening of the just-released Jimi Hendrix biopic in which he stars. He spoke about his current work with the Queen of Soul, how and why OutKast and the Dungeon Family 20 years ago put the city of Atlanta on their backs and what young musicians now can learn from his group's early days. Tonight OutKast begins a three-night stand in their hometown, after which they'll continue a months-long festival tour.

MUHAMMAD: What's good, man. How you doing?

ANDRE: I'm good. I have no complaints, man. Just happy here to be here, alive and considered.

MUHAMMAD: Well, we're happy that you consider rocking with Microphone Check. Really happy to have you here.

ANDRE: Well, thank you, man. It is a honor. Stank you very much.

MUHAMMAD: Just a moment ago — I want to go back — cause you just said something that bugged me out. You working with Aretha Franklin? You don't have to talk about it, but you were just saying that.

ANDRE: Yeah, yeah. That's no problem at all, man. It trips me out, too, still when I think about it.

MUHAMMAD: You playing piano with her?

ANDRE: No, no. I wish I was playing piano. I'm not that good at all, man --

MUHAMMAD: B.S.

ANDRE: Kevin Kendricks — the piano wizard Kevin Kendricks — is actually playing on the song. She's doing a new album where she's doing, like, diva hits. So she's doing — it's like a covers album. And we actually picked a song. We picked a Prince song and she killed it.

MUHAMMAD: Of course.

ANDRE: We just finished the song about a — about a week-and-a-half ago in Detroit, and it was just amazing to, you know, be able to sit in a room with a lady that's been there since the '60s, killing it.

MUHAMMAD: What was that like in terms of, like, phone call, or just the idea of, you know, when you knew that was going to happen? What went through your mind?

ANDRE: It's kinda weird because I hadn't been on the scene, you know, producing, since I've produced OutKast records. So it's not like I'm a hot producer or anything right now, I have all hits on the radio, so when I got the call I was honestly surprised. Clive Davis, he just reached out of nowhere and said, "Hey, we're doing this Aretha album and I want you to work on it." And I was kinda, like, happy, grateful, you know. Like, "Hell yeah, I'll try it."

He gave me the freedom to pick which song that we wanted to cover. We went through a few songs — and Aretha had to agree on the songs — and we finally settled on "Nothing Compares 2 U," which is a Prince song.

KELLEY: That's crazy.

ANDRE: It's a completely different take on the song. You'll — it doesn't sound like any other of the — it doesn't sound like the Prince version. It doesn't sound like the Sinead O'Connor version either. It's Aretha in a different element, but something she's familiar with. But it was really really fun doing it. And just to hear her use her voice like this instrument. She just came in the studio and really just knocked it out in about an hour. I think it was about an hour, yeah.

MUHAMMAD: Have you ever seen her perform?

ANDRE: I've never seen her perform, ever in my life. If my mom was still around, she'd probably trip that I was in the studio with Aretha Franklin.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, I'm tripping.

ANDRE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: I'm sure your mom is definitely like ...

ANDRE: Oh yeah.

MUHAMMAD: I've seen — I saw Aretha Franklin and Gladys Knight at the same time.

ANDRE: OK.

MUHAMMAD: With the Isley Brothers. I don't even know what I — it was just one of those weird moments of like — it was put together as like the oldies kind of a show in New York City, at Madison Square Garden. And for the life of me I just was like, "I'm gonna go see that."

ANDRE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: Cause I'd never — I've seen the Isley Brothers before — but never Gladys Knight and never Aretha. So, it just blew my mind.

ANDRE: Yeah, I can imagine. Just in the studio, working with her, as soon as she got on the microphone and started warming up — just doing, you know, her little runs — I was sitting there smiling from ear to ear, like, "I'm actually in the studio recording Aretha Franklin." Yeah. That was amazing.

KELLEY: I wanted to ask you about that feeling that people have when they meet their idols, their legends, the people that kind of throw them back a little bit.

ANDRE: Right.

KELLEY: How do you feel when people approach you like that?

ANDRE: It's a weird feeling, but then it's such a gracious feeling. Because I know, just being a human being, that we're all really just human beings and kinda acting on stuff that we just tried to do from high school. So we all know that. It's like we just messing around and trying to make something cool.

You look forward 20 years later, and people are, you know, talking about it in a certain kind of way. It's just — it's actually fun because I'm actually standing outside of it, looking at it, looking at other people talk about it. Cause I'm outside of it too now. Because when we were doing it, we were in it. You wasn't worried about, you know, what people were talking about in that way. You just kind of having fun. You in the studio and your whole focus is doing this music. So when it's years later, it's kinda like you're kinda removed from it, and kinda stepping outside of yourself looking at it. So it does feel kinda weird, like talking about a third person.

But I do understand it because I'm a fan of music, so I look at others in the same way. And, you know, just hanging out with people that I love — I mean, we sitting here with Ali. Still, to this day, A Tribe has been — I can — I'm — y'all can't hear my smile right now but, man, like, in high school, you just don't understand how much that meant to me. So when I met you guys, man, it was just crazy. Still, to this day, I'm like, "Wow. These are the guys that really turned me on to this thing." And so I understand what it means to be a fan and into somebody else's music, so I kinda like, I just take it. You know what I mean?

KELLEY: Yeah. What about the additional — I don't know. Maybe it's — is it a burden, maybe it's not — of representing a city? I mean, Tribe has had that in some ways also, but I understand when you were starting out you may not have thought about, like, "I need somebody to rep my city, especially where hip-hop is right now." Was that conscious?

ANDRE: Yes. As a crew, we knew, in our heads, that we definitely wanted to represent the city. And not just the city, we wanted to represent the Southern lifestyle. It was strategic in naming the album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, cause we knew — we all grew up on New York hip-hop. I remember being in the 8th and 9th grade, and we were so into New York hip-hop that we had learned the accents and everything, and trying to imitate New York hip-hop.

KELLEY: Right.

ANDRE: That's just how it was. It's kinda like punk bands trying to imitate English accents to do a certain authenticity. But you kinda grow from that. And so, the first album, when we were dropping into it, as a crew, we knew what we had to represent.

It was a big part, to make sure the city was on our back at the same time because, you know, before then we did have great talent come out of the city but not in a quote-unquote hip-hop kind of form. We had great artists from TLC to Kris Kross and, you know, those kinda acts. But it was something a little bit different when we came. So we was just happy to be a part of it. We were just happy to — as a crew — just to have something to say and to look at people from the city and they have pride in they chest and stick they chest out a little bit different now, because Atlanta kinda means something. So, that was a big part of what we were doing.

KELLEY: What does Atlanta, and Southern culture, mean to hip-hop? Why is it necessary?

ANDRE: I look at it like this — and this is just my opinion — I think it's one of those places where, because we didn't grow up in New York, because we didn't grow up on the West Coast, we had time to soak both of those things in. Because no one expected anything from the South, except, you know, maybe fast, booty-shake club music. The door was wide open, so we had an open palette. And one thing I can say about Atlanta is you can do anything from Atlanta. Like, I think it would've been harder for us to come out from New York because they would've expected us to do a certain thing. We would have to be bound to a certain thing. We would have to rap a certain way, you know. So I think Atlanta is almost like a freedom land because we had no ties to anything. It was just open, like, open field.

KELLEY: What was your experience of OutKast, when you first heard them?

MUHAMMAD: I thought it was something from, like, the Bay or something.

ANDRE: Right. But it was — it's rightly so, though. And I have to — I have to — give a shout to the Hieroglyphics crew and Souls Of Mischief because as kids we were hugely influenced by them. Like they actually — when it comes to rap, I would say Tribe and Hiero — and Das EFX, people don't mention them a lot — but, to me, it was about who had the most interesting things, interesting flows. And, when it came to that, you know, Tribe had their thing, Hiero had their thing, Das EFX had their thing that was different from everybody else. So when we came out, you definitely could hear the West Coast influence in our rhymes.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, but there was something else to it. And I couldn't figure it out until I bought the album and I just was blown away. Hearing OutKast — to me, it didn't sound foreign. It sounded familiar.

ANDRE: Right.

MUHAMMAD: And wholesome and good. I just rolled with it. It's funny, one of my favorite songs is "Mainstream." I don't know what it is about that song that's just — everything is just so colorful and just filling. And takes you on a journey.

ANDRE: That's one of my favorites as well, man. Just the way it was put together. I think Organized Noize — man, that was kinda like one of their shining moments, you know, when it came to production. Even just that — that time signature was just — it was everything to me. Yeah, that was second album.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah. How do you deal with — do you consciously focus on going outside of regular four-four or — you seem really open and just going with it. I'm curious as to, like, the method.

ANDRE: I'm open. As a producer — I didn't start producing until the second album. Our entire first album was produced by Organized Noize — but me, personally, as a producer, I'm just looking for the next thing that's gonna excite me. It doesn't have to be a certain thing. It has to always be moving forward, I say for myself. It just has to be new to me. It doesn't even have to be new to you. Just new to me. And, at that point, I get excited. And that's kinda the fuel of what it is.

Time signatures I'm really — I love when I hear different time signatures. It's funny you say that because I had to tell Aretha Franklin that she — the song "Say A Little Prayer" had a lot to do with the song "Hey Ya." They're similar. It's hard to explain, but listening to that song, the way the loop comes back around, is kinda how I devised "Hey Ya." And I had to tell her that, that she is a big part of that song.

I remember finishing "Hey Ya" and letting Big Boi and Killer Mike hear it — you know, they were riding in the car — and they were digging it, digging it really hard. And I think Killer Mike — I think he wanted to rap on it at the time. I knew Killer Mike would kill it, but I knew it would make it different, it would make it a different kind of song. At that point, it would make it a rap song. And I didn't want it to be a rap song cause I think it would've been — it would've been put in a different category. That time signature — I would've liked to hear what a rhyme would sound like on that time signature.

MUHAMMAD: Your cadence and flows — you move around, you go in between a rhythm, so that's why I was curious about your approach in putting together songs. But, speaking of merging genres — cause that's how I take it — how important is that as, you know, coming from representing Atlanta hip-hop, and putting a stamp on it but then moving beyond that label.

ANDRE: I think — here's my thing about representing a place: The best way to represent the places where you from is be yourself, completely. And just say, "I'm from this place." It doesn't mean I have to cater to that place, you know, cause my thing is taking the city on its back and going beyond. It's not staying in — just in — the city sound. My thing is just pushing it as much as I can cause that's how — that's what gets me off. That's what I do.

But when you listen to Atlanta music now, you listen to trap music — we didn't necessarily come from that, but I love that kind of music. It's funny people say OutKast has this Atlanta, Southern sound. I honestly don't think we ever had an Atlanta sound. I think our accents were from the South. People knew we were from the South. But I can't say that we just had a Atlanta sound, you know what I mean? I think ours was just all over the place. It was kinda like a hodge-podge of whatever we were into.

MUHAMMAD: But I — as an outsider, it was something new. So it seemed like you established it. You know what I mean? Like it became — it's your sound.

ANDRE: Yeah, I think that's what it's about. It's about finding your own thing and adding it to the pot. And we are influenced. You can hear Atlanta's sound in it, but it's like, we don't want to stay there. You know what I mean? It's more important for us to push it.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

ANDRE: Me, as an individual, I get off on that. Like, if I'm not pushing it, or myself, I kinda feel like, "What am I doing?" Cause there are so many great people that can do that thing so much better than I can do it. So why sit there? But I know I'm good at pushing it.

MUHAMMAD: We like it when you push it.

ANDRE: Well, thank you, man.

MUHAMMAD: I'm just saying.

ANDRE: I feel best when I'm doing that.

MUHAMMAD: I identify with that. Me personally, I get — I feel caged when I can't just play whatever I want to play. Be it from the DJ pit or at the drum machine. I just want to express and be whatever it is that come out, you know. Just go with it. And when I find, even myself, that I'm like — as much I try to, not necessarily go outside the box, I just try to exist and be me completely and let it flow — but then you are in situations where people try to bring you back to this area that they like and they're familiar with and they're comfortable with.

ANDRE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: And it is most frustrating.

ANDRE: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: Then I don't put anything out and then people are like, "Yo, what you been doing?" I'm like, "Oh, come to my crib! If you really want to know. Cause I been doing things. I been having fun."

ANDRE: Yeah, that's what it's about. But I mean, we creatures of habit so, you know, most humans, they want something they familiar with. And I totally get that, man. But at the same time, people don't know what they want until they get it. And they're like, "Oh, OK. I kinda dig this." I think Steve Jobs said that best. You can't really ask people what they want. You just gotta give it to them. And then at that point they know they want it. And there's so many great artists that are giving people what they want.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

ANDRE: What's that great — that '70s song — "You Gotta Give The People What They Want"?

MUHAMMAD: [singing] "You got to give the people." Word.

ANDRE: I think there should be a second part to that chorus. You know what I mean? You can give the people what they want sometimes, but sometimes you gotta give them some more, just a little bit more. And if they don't like it, you know, that's cool. I'm fine with people not liking it. Cause it's a lot of stuff I don't like. It's artists that I love that I don't like certain stuff they do.

MUHAMMAD: True that.

ANDRE: So I'm fine with that. It's kinda like, if somebody's liking everything you do, something is probably wrong. Probably. Probably. Yeah, something's wrong.

KELLEY: Going back to categories and "Hey Ya" and what it would've been if Mike had been on it — can you just talk about how Mike being on there would've changed the category and why you didn't want it to be one thing?

ANDRE: People would've labeled it a rap song.

KELLEY: Right. And so why would that have been something that you didn't want to have happen with that particular song?

ANDRE: Cause at the time rap wasn't as interesting — and that whole album I didn't rap a lot on it. Rap just wasn't feeding me at that time. And I knew that I wanted to go beyond it, like the songs that influenced me. I wanted to try just other things and I knew if it had a rap on it, it would've — I mean, I know Killer would've killed it — but at that point, it would've been just another rap song. But it's funny, when we put out "Hey Ya," at one point, we didn't even label it. We didn't even tell the radio who it was. Because if we would've put OutKast on it, at first, it would've been judged differently. And I feel that way about if a rap was on it. You know, some people actually don't like rap. That's just the honest-to-God truth.

KELLEY: Right.

ANDRE: I've met people in the street that said, "You know what? I really don't like rap but I like OutKast."

KELLEY: Ah ha.

ANDRE: It's kinda one of those things where it's taste. That's what it is. You gotta pick and choose. When you're making a recipe, you can put garlic in everything, but sometimes if you going for a whole nother taste, you gotta go all out. And that alienates a few people, which that's — I'm fine with being alienated. But the goal — the goal was to keep this certain kind of energy.

KELLEY: Ah. Yeah. Well, it's my dad's favorite song of all time.

ANDRE: Ah, that's cool. Tell him I said what up.

KELLEY: I will. I will. I can't believe you guys made "13th Floor/Growing Old" when you were so young.

ANDRE: Yeah, yeah.

KELLEY: How did you come to be — your whole crew, all of the Dungeon — so aware and responsible and kind?

ANDRE: It's hard to remember back on those times. I just know we would sit around and just talk all the time. It was really starting with, sometimes, conversation. And sometimes it may be — you know, Rico may have heard me say a rhyme. I may have said something that stuck out to him, and he would pull that part. Like, "Ah, man! Yeah, yeah, yeah — that part." Even the title, ATLiens, that was from an earlier rhyme that I wrote. I said something, and I said, "Blah blah blah blah ATLien." And Rico's like, "Ah! That word. That's a dope word." And at that point, that became the album title.

So it's kinda that thing, and I think with "Growing Old" — I think it may have started with this chorus that was kinda raunchy. And I think Rico took it from there and made it bigger than what it was. It was something about "Fat titties turned to tear drops." I can't even remember the rhyme. I mean, that's embarrassing, you can't remember your own rhymes but, you know, that was long ago. But I think he took those words and felt them in that way. And there was — I think Ray was there playing these chords. And it just came together. But it started — it all starts — as conversations. And it goes from there.

KELLEY: Right.

ANDRE: So I think that maturity or, at that time — and Rico and Ray, they're older than we are so, you know, they may have heard something in it that, at that age, we may not have even been into. But then when you get guidance, you kinda — you go with it. When we were that young, Organized Noize and Ray and Rico and Pat, they were really kinda like big brothers, and they really guided us a lot and were super influential in everything OutKast.

Even helping me find my voice, my rap voice. Cause I was coming from a young kid that was watching Redman and those guys and Das EFX and people act crazy. So I was like, "Well, I gotta rap as loud as they rap." And then one day I'm just in the studio on the microphone and I'm sitting there and I was just kinda talking. And Rico was in the control room. He's like, "That's it. Right there." And I was like, "What are you talking about?" He's like, "Your normal talking voice is your rap voice." So those kinda things helped. And I think that song was "Crumblin' Erb," when Ric did that. So it's kinda like those little pointers help you out, when it comes to shaping you.

MUHAMMAD: Are you familiar — I'm sure you are — with Raury?

ANDRE: Of course.

MUHAMMAD: They have this thing, where I think they have like this age limit on who's in their circle. And you just said something about your origins and the guys being older and that being instrumental in, I guess, guiding some of the ideas that you putting out there. Could you speak a little bit to this idea that those who are older can't really show you or teach you or give you anything new?

ANDRE: Oh, no, man. That is so wrong. That's completely wrong. Once again, it's that conversation thing. I think — youthful energy is gold. But age and wisdom is like gold and diamonds put together. So it's like an older person may not have the same fire as he used to have, but he's been there. It's almost like a boxer that's older. He's fought a lot of rounds so he knows how to move, where to move, but someone that's younger may have the energy to keep up.

So young cats, you can learn a lot from older dudes, but I can also say this: Sometimes old people are curmudgeons. They can be set in their ways and stunt youthful growth, you know, because they just didn't go down that path. Even with my own son I try to make sure I'm not teaching him a certain thing just because I was taught it, you know. I just try to make sure was it right or ...? It's kind of a hard balance to do because you want to have the experienced guidance, but sometimes your experience may have been wrong. You know what I mean? That's just the truth.

And I think, with the youth, it's about — I think the old people really have to tell the youth that it's about y'all, man. And I think, as artists, don't worry about impressing the older cats. Don't do that. Because the older cats, they're impressed when you're as young and wild as you can be because we were as young and wild as we could be. Like, don't grow up too fast. Don't grow up and it just — don't try to impress the old people. Be yourself, man.

I think it's the duty of all young artists to kinda, no disrespect, but to say, "Man, f--- y'all." The people that were before me. Cause that's what I would enjoy. To me that keeps — no, honestly — that keeps the music going. If you got a whole bunch of people sitting around, trying to be us or trying to be A Tribe Called Quest or trying to be Nas or trying to be Jay Z, you can --

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, it gets boring.

ANDRE: Yeah, it gets boring, man. To me it's about the progression of it. Like, we all learn from somebody. It's almost like learning to speak. You know, when you first started talking, you sounded like your parents. You form letters, you said your ABCs because your parents sung them to you that way. Once you learn how to put letters together and then put words together and then put sentences together, you start to have your own language, you and your buddies. And that's kinda how it is with music.

At the same time, you get these journalists and even other people in the industry that come down on young kids, will say, "Oh, man, you sound like Andre 3000." Or, "He sound like this person." But the thing about it is, they just started.

MUHAMMAD: Right.

ANDRE: You know what I mean? Give them time. So I always say — people who say that, I say, "Man, give them time. Give them time. We all sounded like somebody when we started."

MUHAMMAD: For reals.

ANDRE: Even Jimi Hendrix. They used to talk s--- about him. They say, "Man, he's a fake-a— B.B. King." That's what they used to say. But you gotta give them time to kinda get into they own. That's, yeah, just get into your own, man.

MUHAMMAD: Cool.

KELLEY: That's kinda what this movie is about, right? Is that moment when he figures it out and does come into his own.

ANDRE: Yeah, I mean, and it's — once again, like, we were talking about — the people around us when we were younger that help make us. The Jimi movie is really — that's the core of this movie. About his support system that was around, about the people that nurtured him. Jimi would not be who he was — no matter how great a guitarist he is — he would not be who he was if it wasn't for the young ladies around him, if it wasn't for the other bands, if it wasn't for The Who, if it wasn't for Clapton, if it wasn't for all the contemporaries around him. He would not be who he is.

And I don't care how great you are. I've learned, being in the industry, it ain't really about talent. It's about — like, it's 90% feeling and timing and 5% talent, to be honest. You can be the most talented person in the world, but if you ain't doing nothing with it and you're not connecting with the people or you're not at that moment — it does not matter. So the people around you — use your support system.

MUHAMMAD: Absolutely.

KELLEY: Thank you so much.

MUHAMMAD: Word.

ANDRE: Nah, thank you.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.