Bill Russell, one of basketball's legendary players, has died at age 88. The announcement was posted on his verified Twitter account.

Russell won more NBA titles than any player in history. All eleven were with the Boston Celtics. As a five-time league MVP, he changed the game, making shot-blocking a key component on defense. And he was a Black athlete who spoke out against racial injustice when it was not as common as it is today.

Fighting for something from an early age

To understand this man and superlative athlete, it helps to remember a parent's lesson.

One day when Bill Russell was 9, he was outside his apartment in the projects in Oakland, Calif. Five boys ran by and one slapped him in the face. He and his mother went looking for the group, and when they found them, young Bill expected mom justice. Instead, Katie Russell said: Fight them, one at a time. He won two, lost three. In a 2013 interview for the Civil Rights History Project, Russell said his mother's message to her teary son changed his life.

"And she says, 'Don't cry,' " Russell said. " 'You did what you're supposed to do. [It] doesn't matter whether you won or lost. [What matters is] you stood up for yourself. And that's what you must always do.' "

Russell certainly did on the basketball court — where he blossomed late but ended up revolutionizing the game.

Elevating and taking the game with him

"Krebs from the corner. His outside shot blocked by Russell. And now Russell has made three big plays in the last three minutes of the game. Barnett goes in and Russell blocks it."

By 1963, in this NBA Finals game, Russell was a shot-blocking menace, which represented a sea change in the game.

The adage always had been: No good defensive player leaves his feet. In the 1950s, his coach at the University of San Francisco believed that. But Russell didn't. He was also a track and field high jumper, and it seemed perfectly reasonable to try to elevate in basketball as well.

"My first varsity game [at USF], we played at [University of] Cal Berkeley," Russell said in the 2013 interview. "Their center was a preseason All-American. The game starts and the first five shots he took, I blocked. And nobody in the building had seen anything like that. So they called timeout to discuss what I was doing. We get in our huddle, and my coach says, 'You can't play defense like that.' He showed me on the sidelines how he wanted me to play defense. I go back out and I try it, and the guy [scores on] layups three times in a row. And I said, this does not make sense. So I went back to playing the way I knew how."

"Basically what I was doing, in retrospect, was bringing the vertical game to a game that had been horizontal."

And the results were convincing.

Russell led San Francisco to NCAA titles in 1955 and 1956. In '56 he also led the U.S. to an Olympic gold medal.

And soon after, the start of a historic NBA run.

Love and hate in Boston

From 1957 to 1969, the Celtics won 11 titles, including eight straight. There were great players like Bob Cousy, Tom Heinsohn, Sam Jones, K.C. Jones and so many others.

But none like Russell.

He was the bridge to all 11 championships, a competitor so fierce he'd often vomit before games.

Success, though, couldn't hide a difficult relationship with the city where he played.

Russell didn't trust some of Boston's white fans who'd cheer the winning but then complain the team had too many Black players. In a Boston Globe documentary, former teammate Heinsohn remembered how the Boston suburb of Reading, where Russell lived, held a dinner to honor him.

"He was so taken aback by this honor that was bestowed on him," Heinsohn said, "that he broke down, started to cry, and he said that he wished he could live in Reading for the rest of his life."

But not long after, people broke into Russell's house, destroyed trophies, defecated in his bed and smeared excrement on the walls.

His relationship to those outside the Celtics locker room became chilly. He got a reputation for being surly. He refused to sign autographs, as a way to weed out the "good" fans.

"Russell was the type who had doubts about people's intentions," Stephen Beslic wrote in Basketball Network in 2020, "and [he] didn't want someone using him for his popularity. That's why he offered a simple solution: you won't get anything signed by him, but you will get 15 minutes of coffee time with one of the greatest to ever play the game."

"If a fan doesn't want to have a chat with you," Russell said, "he was going to sell that autograph anyway."

But loving his team

On the other hand, Russell loved the Celtics, and the progressive white people who ran the franchise — owner Walter Brown and legendary head coach Red Auerbach. During the dynasty years, the Celtics became the first NBA team to have an all-Black starting lineup.

And in 1966, more history.

When Auerbach retired he named Russell to take his place, making him the first Black head coach in the NBA. It was historic, but Russell said he didn't care. He simply believed he was the best man for the job.

Although a reporter questioned that, as recounted in the 2013 NBA-TV documentary, Mr. Russell's House.

"As the first Negro coach of a major league sport, can you do the job impartially, without any racial prejudice in reverse?" the reporter asked.

"Yes," Russell said, "because the most important factor is respect. In basketball, respect a man for his ability. Period."

Beyond the court

The Celtics dynasty dovetailed with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and Russell fully engaged.

He sat in the front row at Martin Luther King Jr.'s historic "I Have A Dream" speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. He — along with Black teammates — boycotted a game in Kentucky when a restaurant denied them service. He joined other prominent Black athletes in supporting boxer Muhammad Ali, who refused to join the military during the Vietnam War.

And Russell wrote a book, Go Up For Glory.

"It really changed how athletes wrote about themselves and society," said Damian Thomas, curator of the sports exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

He says the book, part of the exhibit, was a transformational autobiography.

"Rather than just merely sticking to sports," Thomas said, "we began to see athletes offer opinions about race, opinions about politics and things of that nature."

For Russell, speaking out for civil rights and fighting against racism never ended. In a 2020 essay in Slam magazine, Russell noted how George Floyd, who was killed that year by Minneapolis police, was "yet another life stolen by a country broken by prejudice and bigotry."

"But what can we do about it?" Russell wrote. "Racism cannot just be shaken out of the fabric of society because, like dust from a rug, it dissipates into the air for a bit and then settles right back where it was, growing thicker with time.

"Police reform is a start, but it is not enough. We need to dismantle broken systems and start over. We need to make our voices heard, through multiple organizations, using many different tactics. We need to demand that America get a new rug."

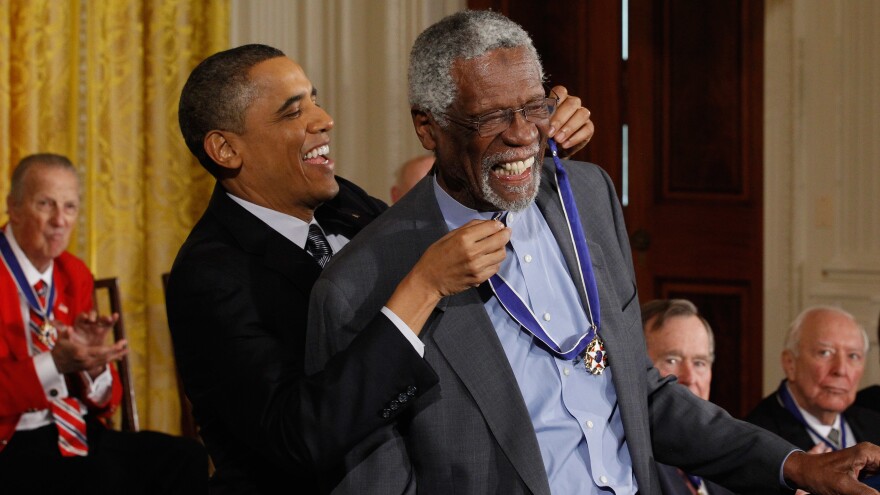

A laugh for the ages

Russell's life was long — at times profound, and at times messy.

He had a falling out with longtime friend and fierce competitor Wilt Chamberlain — Russell didn't like the word rival to describe their on-court relationship. Later in life they reconciled. Russell also reconciled his feelings, somewhat, about the city of Boston.

Through it all, there was one constant for Russell: laughter.

A laugh for the ages. As recognizable a part of Bill Russell as the image of him in his number six Celtics jersey, rising above the court to grab a rebound or swat an opponent's shot. Red Auerbach was quoted as saying one of the only things that could make him stop coaching was Bill Russell's laugh.

But the high-pitch cackle was beloved by many more. And it bore the mark of another Katie Russell lesson. His mother told him never hold back. On anything

And once again, her son listened well.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.