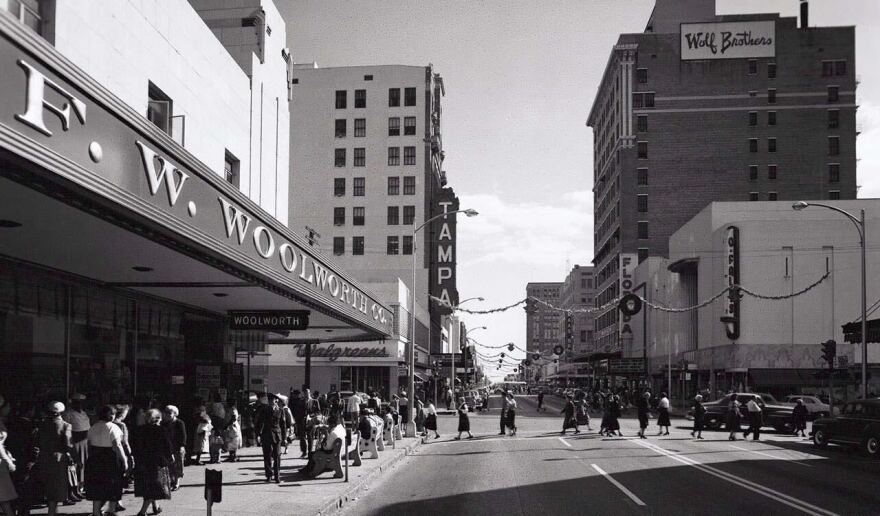

On Feb. 29, 1960, a group of Black high school students bravely entered the F.W. Woolworth department store on the corner of North Franklin and East Polk streets in Tampa.

It was a time during the Civil Rights movement and segregation, and in this instance, Black residents were not allowed to sit at the lunch counter there.

As a show of solidarity, they took part in the first sit-in as a way to unite and say that they did indeed belong.

Over the following week, they were joined by police and politicians who were united in their support during the peaceful protests.

ALSO READ: A salute to Tampa's Woolworth lunch counter sit-in on its 65th anniversary

This inspired a play, "When the Righteous Triumph," which has been performed over the last couple of years at Stageworks Theatre in Tampa.

It also led to a documentary, "Triumph: Tampa's Untold Chapter in the Civil Rights Movement," produced by Tampa PBS station WEDU.

It features interviews with living residents who made that history, including state Sen. Arthenia Joyner, the first Black woman Senate minority leader for the Florida Legislature, along with Clarence Fort, the former president of the NAACP Youth Council.

The film will be screened on Jan. 19 — Dr. Martin Luther King Day — at Tampa Theatre. It will be free, and it's available to watch online for free as well. (UPDATE: All tickets for the screening are now reserved).

On "Florida Matters Live & Local," host Matthew Peddie spoke with director Danny Bruno about the making of the film, the risks taken by the protesters and some of the historical figures who influenced the outcome.

This documentary shows the unsung heroes of sit-in demonstrations in February of 1960. Tell us a little more about them.

Yeah, so so many unsung heroes. We have the participants who sat in, the students from the two Black high schools in Tampa at the time, Howard W. Blake High School and Middleton High School. And so you had 20 students from each school who went to the march to the Woolworth and sat in in 1960, inspired by the movement that started in Greensboro, North Carolina.

For folks who may be unfamiliar with this, Woolworth's had a lunch counter. It was segregated, so if you were Black, you weren't allowed to sit at the white lunch counter. And they were basically rocking up and saying, "We're going to sit here."

Right. You could order your food to go, and you can shop at the rest of the store, but you could not sit down at the lunch counter if you were Black in 1960, and that was pretty much across the country. I think there were some states a little more progressive at the time. That wasn't the case.

But especially in the South, the Woolworth lunch counters — as well as other lunch counters in the downtown areas — that was the situation. So they decided they had enough, and like I said, they were inspired by the movement that started in Greensboro, and it had spread throughout the whole country. Started on February 1 in Greensboro, North Carolina, by Feb. 29, 1960, that's when Tampa decided to start their movement, led by Clarence Fort.

And there was another name that I think is mentioned in the documentary. He was a key part of this as well.

Yes. Reverend A. Leon Lowry was the pastor of Beulah Baptist Institutional Church at the time. And he was also a teacher of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr at Morehouse in Atlanta. And so, at the time, he was working with the NAACP.

Clarence Fort, at the time, was the president of the Student Youth Council. And he went to Reverend Lowry for support, and eventually, he did get his support. And so he rallied these students from the two Black high schools, 20 students from both schools. And that's how it all started.

Did you know before you started researching this that there was this connection with Dr. King and Reverend Lowry?

No, I really didn't know much. I grew up in Orlando, so not too far from here, but I didn't know much about Tampa's history. But this was an opportunity for me to learn.

So, my approach with the documentary, I kind of wanted to approach it as if the viewer doesn't know anything about Tampa, just like I didn't know much about Tampa. And so I was learning along the way. And I was learning all these cool, fascinating details about how this happened. And I was just really inspired by the bravery of these students who took a stand by taking a seat, really, at the lunch counters.

"I was really trying to put myself then and there in that place in time. It really wasn't that long ago. And so it's a great thing that we still have some of these folks with us who can share their stories and tell us exactly what was going on in their minds and why they did what they felt they had to do".Danny Bruno

Because they were putting their bodies on the line, right? Like in some cities, they were getting beaten and arrested and it was dangerous for them.

Oh yeah. That's one of the themes that I wanted to focus on was the sacrifice. Definitely, they put themselves in harm's way. They put their bodies on the line. In other cities, yes, it did turn violent.

But Tampa was unique because we didn't really have much violence here.

And that was because of the leadership that we had. We had a mayor who sided with the demonstrators, Mayor Julian B. Lane, who created a biracial committee composed of different city leaders — like Reverend Lowry, like Cody Fowler. Cody Fowler, the grandfather of Jim Davis, who's a former congressman.

The difference was, here in Tampa, that we had support on the leadership level, and that's how we were able to get the lunch counters integrated. That same year, the movement started in February. There were some negotiations that happened. And then by September, the lunch counters were integrated.

Why do you think this history feels kind of overlooked in some ways, or hidden, compared to other stories about these demonstrations? Like Greensboro, as you've been talking about, or North Carolina, or Atlanta, Georgia.

I think it's important to know about all of our history, right? It's important to know about the situations that became violent, and some of the violence that these folks endured at that time, for just trying to stand up for what was right.

But I think that what's different is that this was a success story, right? It didn't end violently.

And so I think maybe that's part of the reason why this story is overlooked. But we wanted to highlight that. And that's why the documentary is called "Triumph." Because this was a triumph, when the civil rights movement was just kicking off.

You mentioned this play by local playwright Mark E. Leib called "When the Righteous Triumph." How did that kind of help bring this historical moment to life?

We were very fortunate to have that. Because we were able to rely on a lot of the visuals from this great play by Mark E. Leib, and it kind of served as a backbone of the documentary. We were able to refer to different moments that the play actually highlights within the documentary, and so it was great to be able to have that. We were able to use some of the footage of the play that we taped back in March of 2025.

The play actually was produced and released in 2023, and it came back in 2025. We partnered with them early enough to be able to plan to capture that performance. And so it was just great working with them and working with the actors and with Mark and interviewing Mark in the documentary as well. It was just a great partnership all around now.

ALSO READ: A play depicting Tampa’s historic Woolworth lunch counter sit-in runs at the Straz Center in March

There are some moments in the documentary. You're talking to folks, they're holding photographs of their younger selves at the lunch counter. As a storyteller, what was it like, kind of that moment for you, sort of that moment in time?

It's hard for me too, because I'm a crier. A lot of moments almost brought tears to my eyes. Some moments did bring tears to my eyes. So seeing them reminiscing and looking back at old photos.

My inspiration became listening to a lot of music from the '60s. And that became actually an element that influenced the soundtrack of the documentary as well. I was really trying to put myself then and there in that place in time. It really wasn't that long ago.

And so it's a great thing that we still have some of these folks with us who can share their stories and tell us exactly what was going on in their minds and why they did what they felt they had to do.

How did other merchants respond to the sit-in?

What was great about how that was negotiated was here in Tampa, they decided to have all of these different merchants integrate at the same time. That was part of the discussion.

Some of them were worried, "Well, if we allow Black folks to come sit at our lunch counters, then everyone's going to go to the other stores. They won't come to our store anymore." All of the white people at the time who weren't comfortable with sitting next to Black folks at the lunch counters.

But it was done in such a way. The biracial committee, the merchants, there were organizations that worked together to make this happen in a way that was actually beneficial from a business standpoint to do this at the time. And I think they realized that afterward, that this was something they probably should have done a long time ago, and it definitely helped them financially.

But there was some blowback, right? I mean, the mayor lost the reelection.

There was. So again, that recurring theme of sacrifice. So we had students putting their lives and their bodies on the line, but we had leaders who put their careers on the line. Mayor Lane, at the time, he was not reelected. And I believe the same was the case for the governor at the time, Governor (LeRoy) Collins, because of their choice to side with the demonstrators and be on really the right side of history.

They suffered losses when it came to their careers. And we had Reverend Lowry, who literally his home was shot at. Luckily, nothing happened to him. He wasn't hit. But around that time of the sit-ins, his home was shot at. And so, all these folks, all of them made sacrifices in different ways. And we're just fortunate to live in a city like Tampa that really was on the right side of history in 1960.

Portions of this interview were edited for length and clarity.