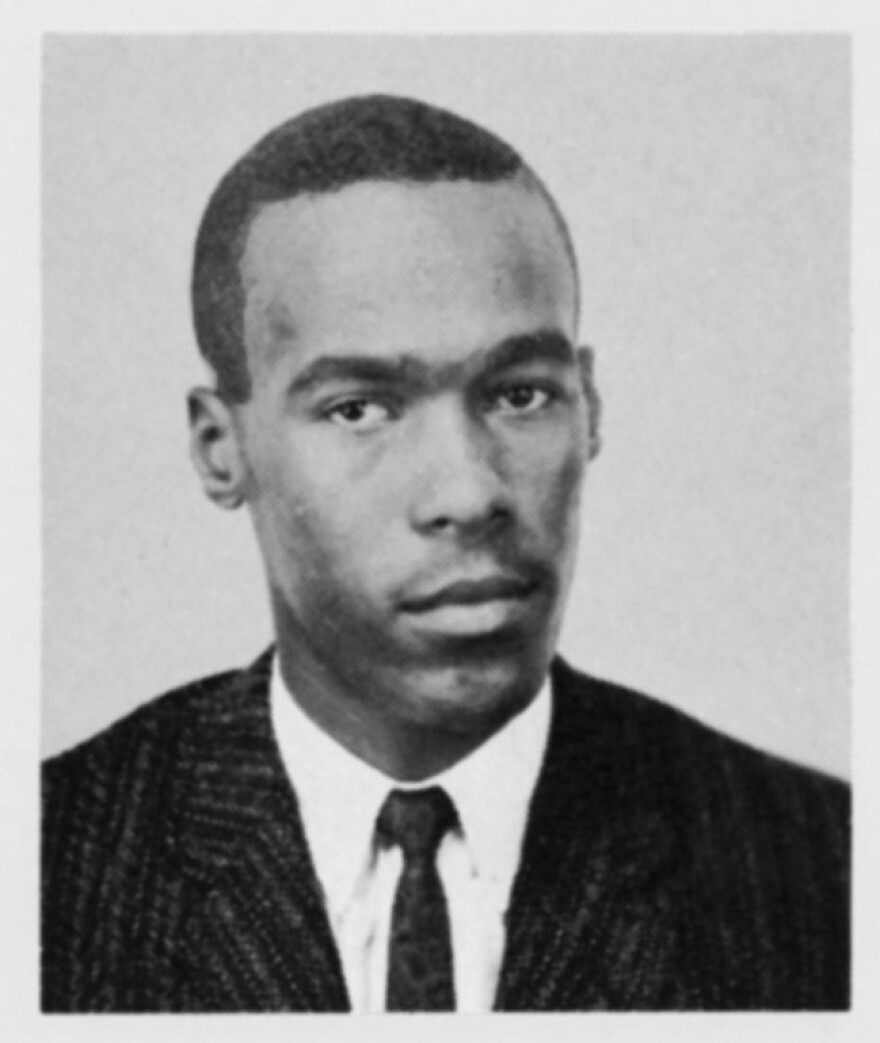

Kent Garrett Sr., 97, still remembers how proud and happy he was when his son was admitted to Harvard in 1959. "I invited everybody over for dinner," he recalls with a laugh.

Garrett was a subway motorman who worked a second job waxing floors. His son, also named Kent Garrett, was among an unprecedented group of 18 black students accepted into the class of 1963.

Garrett chronicles what that time was like for him and his fellow black classmates in the new book The Last Negroes at Harvard, co-authored with his partner, Jeanne Ellsworth.

"We would be attending a school that was founded and funded on the backs of our enslaved forebears ..." Garrett writes. "We were headed to a campus where, until about eighty years before, each student was given a personal Negro servant, a campus that in the 1920s barred Negroes from the dormitories and had a branch of the Ku Klux Klan."

When the time came for Garrett to pack his bags and head to Cambridge in the fall of 1959, he didn't go alone. His parents, his kid sister, a couple of aunts and an uncle filled two cars and went with him. "It was a little bit embarrassing in a way, everybody wanting to come up there," Garrett recalls.

Like the black students who preceded him, Garrett endured indignities and racism once he got there. W.E.B. Du Bois, the college's most famous black alumnus, wasn't allowed to live on campus in the late 19th century. In 1952, a cross was burned outside a dormitory housing 11 black students. During his freshman year, Garrett was tasked with cleaning the dorms — he says it was the "worst job" he could have been given.

"I'd been with my dad, floor waxing in rich white people's houses all those years growing up, and here I was again at Harvard, you know, doing 'Negro' sort of work," he says.

Garrett and Ellsworth decided to use the word "negro" in the title of their book because that was the term used during Garrett's four years at Harvard. By the time he graduated, though, they were calling themselves Afro-Americans.

"They knew something was up — that there were 18 of them there and they discussed it at the black table," Ellsworth says. "You know, 'What's going on here that we're all here?' We know that there are now more of us than there ever had been."

The 18 black students had been accepted in an early form of affirmative action. Sitting at "the black table" during meals was a needed refuge from his white classmates, Garrett says. He was one of just 18 black undergraduate students in a freshman class of more than 1,000. You can read more about each of the 18 students here.

"We were curiosities," he says. Other students asked them the same questions repeatedly: "What is it like to be a negro?" and "What do you people want?" It got old pretty fast.

"After you hear that question every day for X number of days, it gets tiring," Garrett says. "You definitely don't want to hear it, you want to steer the conversation somewhere else."

Garrett became close friends with another black student, Fred Easter, from Harlem. Easter is now retired and lives in Minnesota. He recalls an encounter with one of his white friends in the dining hall.

His friend noticed some uneaten peas on his plate, and asked whether he was going to eat them. "I said 'no,' " Easter recalls, "And I was gonna shovel them off onto his plate. He said, 'No, don't worry, I'll just get 'em.' And he ate off my plate, which was astonishing to me. It spoke to his comfort level, which was a comfort level not widely held by white people in the United States in 1959."

Garrett's book also recounts the time Malcolm X came to dinner at the residence Garrett shared with other students ... and how efforts to establish a student association for Africans and Afro-Americans were thwarted by the Harvard administration.

"As the civil rights movement moved along and Malcolm X came on the scene, I mean, my thinking started to move towards more black power, realizing that this integration thing is probably not going to work," Garrett says.

Garrett's thinking was influenced by a roommate at Harvard who moved to Africa after college. Garrett returned to New York where he worked in advertising before taking a job in 1968 at the public television show Black Journal -- the first national program to focus exclusively on the concerns of African Americans. Garrett went on to become a producer at CBS and NBC but he became disillusioned with network news and left his big city life to become a dairy farmer in the Catskills.

Garrett writes in his book that he still doesn't contribute money to Harvard and that he didn't go to a class reunion until two years ago. Easter has been to several reunions, including his 50th which took place during graduation ceremonies for the Class of 2013.

"There were lots of black students," Easter says. "And one guy called out, 'Look at those guys. That's 50 years.' One guy said, 'We know what you went through. Thank you,' he said, 'Thank you.' "

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.