It's been one month since Florida banned fluoride in drinking water.

Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill this spring that outlawed utilities from adding water quality additives such as fluoride.

Coincidentally, the day before Florida's ban went into effect July 1, Calgary, Alberta, in Canada reintroduced fluoride to its water after stopping the practice 14 years prior. One of the big reasons why Calgarians voted to once again add fluoride to water was an eight-year study showing significant increases in tooth decay in second-grade children.

What happened in Calgary?

In 2011, the Calgary City Council voted to remove fluoride from its water system, citing costs. Leaders said improving the system would be too expensive.

"How do you put cost on people's health in a budgetary item?" said Dr. Bruce Yahlonitsky, a Calgary dentist. "Then we see the deleterious effect of what's happened."

The practice of fluoridating water began after an experimental trial in the 1940s in Grand Rapids, Michigan, showed favorable results in children fighting tooth decay.

According to Yahlonitsky, two years after fluoridation ended in Calgary, he started noticing more rampant tooth decay in young patients.

"We were seeing kids who had never been exposed to any fluoride in the water," he said. "And when you've got kids that are even under 2 years of age, who have all their teeth with decay on them, you have to take them into a hospital situation to treat them. They can't be treated properly in a dental office."

But was ending fluoridation the reason?

The study

Before the 2011 council vote, Lindsay McLaren didn't know much about fluoride or dentistry.

"I really knew nothing about teeth. I didn't even know how many teeth we had," she said.

McLaren is a community health researcher at the University of Calgary. She began looking into the research on fluoride and was disappointed to find that there wasn't more new information.

"I was a little bit surprised it wasn't as strong as it's often felt to be by those in the public health community," she said.

McLaren realized there was a golden opportunity for research. She decided to conduct her own study, which was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

She, along with a team, compared second-graders from Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta's capital, where fluoridation had been in place since 1967.

Over nearly eight years, McLaren and the team compared the dental hygiene of second-grade children from both cities, and then compared those results against historical data sets from 2004-05 as well as 2009-10. They also sent questionnaires home to parents asking about diets and dental hygiene routines.

Lastly, they collected a small sub-sample of fingernail clippings as a fluoride intake biomarker. The fingernails were used almost like the dipstick in a car, checking the oil level.

"This is quite important, because fluoride intake, based on the fingernail clippings, must be lower in Calgary than it is in Edmonton. And if it's not, then something really significant has happened to offset the lack of fluoride in the water in Calgary, right?" she said.

And after eight years, what McLaren and her team found was cavities occurred more in the sample of kids from Calgary.

While about 55% of kids studied in Edmonton had tooth decay, in Calgary, that number was around 65%. Historically, children from both cities had around the same percentage of decay issues.

"It's a statistically significant difference, so it's not likely to be due to chance," she said.

The study highlighted another issue. Simply fluoridating water is not enough. Kids in Edmonton, where the practice has been in play, still had high levels of tooth decay.

"This makes it very clear that fluoridation is clearly not the only thing that's important here, but it's still important," McLaren said.

Income inequality is high in Alberta, according to McLaren's study, and significant social inequities in a child's ability to access dental care exist, exacerbating the issue. In other words, no longer adding fluoride to water could lead to a rise in tooth decay, depending on the setting, McLaren said.

In 2021, the question of whether to resume fluoridating in Calgary was put to a referendum, and 62% voted to reverse the 2011 city council decision. It would take another four years to put the infrastructure back in place.

Will Florida be like Calgary?

McLaren says it's too early to predict whether Florida will experience similar dental health concerns as Calgary, which has a population of about 1.4 million.

"You may not need fluoridation because you're providing the conditions for people to be well otherwise," McLaren said. "To the extent that describes Florida, maybe it'll be fine, but I'm not sure that describes Florida."

That's something that concerns University of Florida researcher Dr. Olga Ensz. Her work focuses on dental deserts in Florida.

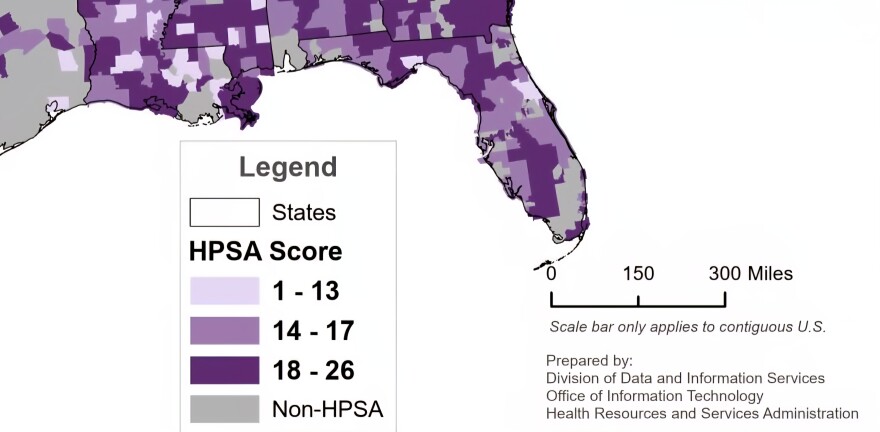

"Sixty-five out of our 67 counties are considered dental health professional shortage areas, which means there are not enough dentists to serve the population in those communities," Ensz said.

Florida dental records by the numbers

Florida ranks 45th nationally for dental care, with 5.9 million people residing in a dental desert, according to KFF.

The federal Health Resources and Services Administration also found that Florida has 274 designated areas facing dental shortages, or communities that don't have enough dentists for the population. According to the HRSA, that's about 5,000 people for every dentist.

Data from the Florida Department of Health also shines a light on the state's dental issues, with nearly one in three third-graders having untreated tooth decay during the 2021–22 school year. It's almost double the national average of 17% of children ages 6-9, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And in 2020, Florida had the highest rate of nontraumatic dental condition emergency department visits for those 14 and younger compared to all other states, according to the CareQuest Institute for Oral Health Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project dashboard.

Historically, emergency visits for dental have gone down in Florida, but between 2021-23, every county in Central Florida reported increasing visits to the ER for dental conditions 5 and older, health department records show. Marion and Volusia showed the greatest rates of increase.

Is fluoridated water the answer?

One of the reasons why children are the focus of fluoridated water studies is because of their exposure to sugary foods and the vulnerability of young teeth, Ensz said.

"They have less enamel on the outside, and so they're a lot more prone to getting cavities," Ensz said. "Especially when dental hygiene might be poor and when they do have challenges with accessing dental care."

However, she's not convinced community water fluoridation is the only way to address tooth decay.

Ensz said reducing the consumption of sugary foods would go a long way in addition to proper brushing and flossing, and seeing a dentist even if only once a year.

As for those without immediate access, Ensz said the state would need to invest in dental health programs, similarly to countries that don't fluoridate, such as Japan, and practice fluoride-mouth rinsing with preschoolers.

Several Florida counties do have school-based dental sealant programs, in which a dental provider will apply an inexpensive fluoride varnish, Ensz said. She's hoping the state will make up for fluoride cessation by investing in similar programs.

"This is something that will require a lot of support," she said. "This will be a challenge until we can really demonstrate through our policies, through our insurance, that oral health is part of overall health. And I think how our system is right now, it's unfortunately putting dental health in a silo, and that will lead to these issues, I think, to continue."

How Florida became the second state to end fluoridation

The day after Florida's fluoride ban went into effect, Orange County resident Justin Harvey held a glass of water in the air, surrounded by a group of people, all beaming with smiles.

It was a celebration for their hard work over the last several years to convince municipalities to remove fluoride from drinking water.

"Thank you so much for being a part of this journey," he said at the Florida Water Bar/Refill Station, an Orlando buisiness that sells purified water. "This is a cheers to a healthier future, and on the count of three, let's just say fluoride-free."

The crowd echoed his toast in the small Water Bar, which sells alkaline water, which has a higher pH than typical bottled or tap water, can be naturally occurring and contains minerals like magnesium and calcium. Some research suggests alkaline water has multiple benefits, such as improving muscle and bone quality, but overall research is divided.

As for the group, they were jubilant.

"This is a very gratifying day that we've been waiting for for a long time," Harvey said.

Harvey and others like him became concerned about fluoridated water after learning about studies linking the mineral exposure to lower IQs and calling it a "forced medication."

While fluoridated water has always been a hot topic, the subject received renewed attention last year when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. , who would go on to be Health and Human Services secretary, spoke about ending the practice. Soon after, Florida Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo issued guidance on ending fluoridation, citing the studies on IQs.

That concerns were identified in the National Institutes of Health's National Toxicology Program: a meta-analysis, or systematic review, of existing epidemiological studies on fluoride exposure's potential cognitive impacts on children. Most of the studies reviewed were from China and none from the United States. Most were deemed to be low-quality, meaning they had a high risk of bias. However, the rest were deemed high quality and low bias.

Last year, the meta-analysis was referenced by a federal judge who relied upon it in his ruling in favor of an anti-fluoridation coalition, which sued the Environmental Protection Agency in 2017.

All of that built the momentum for Harvey and other fluoride-free friends to speak with city and county leaders, convincing them to end the practice.

That momentum swelled with the most recent Florida legislative session, which passed a bill (SB 700) that DeSantis signed in May.

Calgary's return to fluoride and McLaren's study do not concern Harvey.

"Most of the developed world doesn't fluoridate its water, so a lot of people worry about what the consequences of this could be. Are teeth going to rot? But the majority of places that remove it, or have never had it, have no issue," he said. "In my opinion, we take the medicine out and there's no drawback."

As for what's next, Harvey is looking at other states.

This year, Utah became the first state to ban fluoride. There have been movements in other states, like Arkansas and Kentucky, to also remove it, but the efforts failed. This month, Connecticut signed legislation to keep fluoride in its water.

"Our entire goal is to replicate this for other states and let other states do what we did. So we want to see that that's what we want to push. And I'm just happy to see that other states are encouraged by this," Harvey said.

Copyright 2025 Central Florida Public Media