Fifty years ago one of the world's most notorious war criminals sat in a courtroom for a trial that would be among the first in history to be completely televised.

That man was Adolf Eichmann — and he had been in charge of transporting millions of European Jews to death camps.

A year before the 1961 trial, Eichmann had been abducted by Israeli agents while he was living in Argentina.

The trial captivated millions of people. And it was the first time many of them — including Israelis-- even learned about the details of the Holocaust.

Now Deborah Lipstadt, renowned historian and professor of religion and holocaust studies at Emory University has written a new account of the trial. She tells All Things Considered weekend host Guy Raz that the Eichmann trial was different from any other war crimes trial because it featured the stories of Holocaust survivors and captured the emotions that weren't a part of the document-heavy Nuremberg Trials, which took place more than a decade earlier.

Survivors Stand Up

"There was a march of survivors, I would say approximately 100 survivors, who came into the witness box and told the story of what happened to them. And people watched them and listened to them and heard them in a way they hadn't heard them before," Lipstadt says.

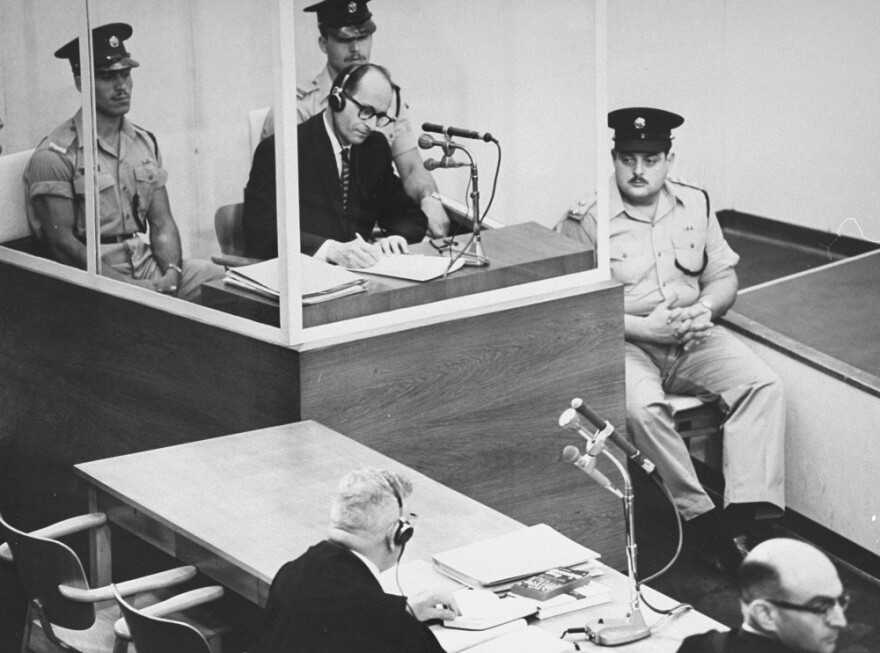

Hearing the voices of survivors wasn't the only aspect of the trial that shook the audience; seeing Eichmann was unnerving as well. This man, who most Israelis considered one of the greatest murderers of all time, appeared so normal.

"People were amazed because he looked much more like a bureaucrat, like a pencil pusher, [with] thick black glasses, an ill-fitting suit, a man who laid out all his papers and his pens and kept polishing his glasses with a nervous tick," she says.

Lipstadt says people asked themselves, could this really be the person responsible for the destruction of millions?

But Eichmann's testimony, says Lipstadt, illustrated not only that he was guilty, but how "enthusiastic" he was about carrying out his orders.

"There would be times when he would get a communique from the German Foreign Ministry saying the Italians have contacted them and there's a Jew in Vilna, or a Jew someplace else in a ghetto who's married to an Italian Catholic ... and Eichmann would quickly rush to get the man deported, sent to Auschwitz or hidden away so that he couldn't be turned over to the Foreign Ministry and maybe escape. He went after every individual Jew he could find," Lipstadt says.

One Man's Sentence, A Society Transformed

Even after Eichmann was found guilty, the question remained as to whether or not to sentence him to death.

No one in Israel had ever received such a punishment, and even Israel's prime minister at the time, David Ben-Gurion was opposed to the death penalty.

So when one of the judges stood up at the end of the trial and said "By Israeli law we are not required to impose the death sentence," people thought for a moment Eichmann might only get life in prison.

But the judge continued, "We are not required, we may impose it, and we chose to do so because you are deserving of the death sentence."

The Eichmann trial affected people across the world, but Lipstadt says it may have had the greatest impact on the younger generation of Israelis. She says it showed them the importance of the existence of the state of Israel.

"Had there been a Jewish state, it might not have been able to stop what was going on, but one of the reasons many of the people who were murdered were murdered was because they had no place to go. And Israel would have been a refuge," she says.

The trial was also a reminder that the Holocaust's victims had names, faces and histories.

"The Holocaust didn't happen to numbers or just a large group. It happened to people," Lipstadt says.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.