More than 30 years ago, Robert Farquhar stole a spacecraft.

Now he's trying to give it back.

The green satellite, covered with solar panels, is hurtling back toward the general vicinity of Earth, after nearly three decades of traveling in a large, looping orbit around the sun.

If Farquhar, a former mission design specialist for NASA, gets his way, the agency will command the spacecraft to fire its thrusters, veer close to the moon, and slip back into the spot where it was intended to be when it was launched in 1978 — and where it was when Farquhar and his accomplices "borrowed" it.

Back in the 1980s, space agencies were racing to Halley's comet. But NASA wasn't going — officials said a comet mission was too expensive. That did not sit well with Farquhar, who had dreamed of achieving the first comet encounter ever.

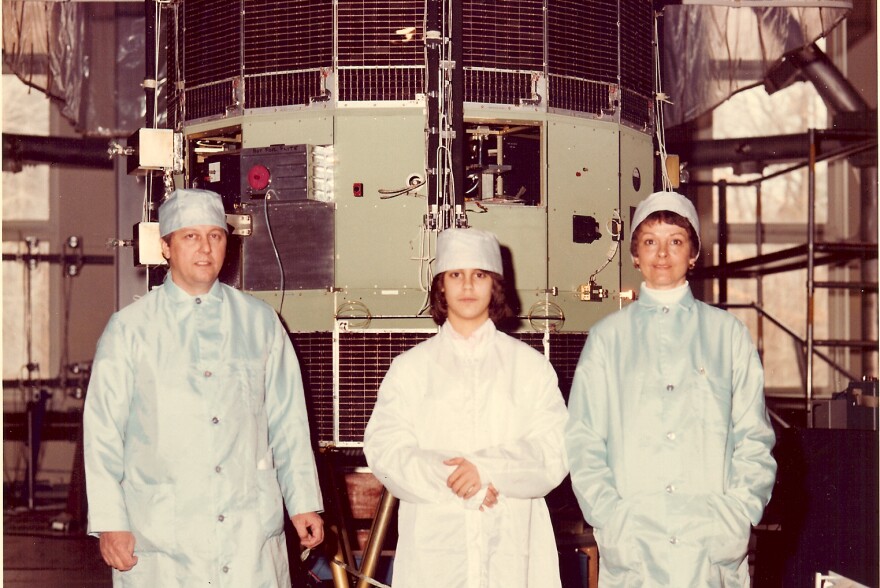

So he figured out how to divert an existing satellite, called the International Sun-Earth Explorer-3 (ISEE-3), that was stationed between the Earth and the sun in an innovative halo orbit that he had pioneered.

Farquhar came up with a complicated trajectory that would let this spacecraft intercept a different comet called Giacobini-Zinner in September of 1985, months before the armada of other space probes would arrive at Halley's.

"We beat all the other countries of the world," recalls Farquhar. "The European Space Agency. The Russians. The Japanese."

President Reagan even sent him a congratulatory letter.

But some of the scientists who'd been using ISEE-3 to study things like solar wind were not amused by the comet caper.

"They thought that — it was in the newspapers, even — that we stole their spacecraft," says Farquhar. "We didn't steal it; we just borrowed it for a while! That's what I tried to tell them."

After all, he notes, the spacecraft was set on a course that would eventually bring it back.

"OK, so we took it away in 1983 and you get it back in 2014. How many years is that?" says Farquhar, quickly calculating. "Oh, that's about 31 years."

Farquhar is now 81 years old. He's been called the master of getting to places. His genius is inventing esoteric flight plans that take advantage of gravitational boosts from the moon and close flybys of Earth to send space probes zipping around the solar system in surprising ways.

He's so adept at calculating these exotic trajectories that often, just for fun, he's made sure that key mission events fall on birthdays or anniversaries.

The exploits of ISEE-3 were the first ones to really show off what Farquhar could do. "Certainly all the people in the space business know that that's my spacecraft. It's very personal with me," he says.

His memoir makes it clear how personal. For example, Farquhar writes that when he was hospitalized after a heart attack, the spacecraft suffered a battery failure — making him believe they shared a "supernatural connection."

"It's my baby," says Farquhar. "It's something I worked on for a long time and I had to sell it to NASA, and sell it to a lot of people."

What Farquhar is selling now is the idea of waking up this old satellite and doing what he promised.

There's a short window in the next few months, before August, when ISEE-3 could be commanded to slow down and follow a flight path that would return it to the spot where it was stationed before it went off chasing comets.

"It would not just be a curiosity. It would actually be a useful scientific tool," says Daniel Baker, director of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado.

These days, other satellites monitor space between the Earth and the sun, says Baker. But he believes ISEE-3 could provide additional measurements that would be valuable.

"It's not often that something that you've sent off supposedly into oblivion sort of comes back to you," says Baker, who worked with data from ISEE-3 when he was younger. "It really, to me, is a fascinating thing that we can even dream of reassembling the puzzle here and put it back the way, sort of, it was — before Bob stole the spacecraft."

But waking up an old spacecraft, as though it were Rip Van Winkle, is not easy.

"No other spacecraft has been what you might call asleep for such a long period of time," says Edward Smith, one of the scientists who worked on the mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "I'll believe it when I see it, but it's an exciting opportunity and I'm taking it seriously."

People have been scrambling to see what's possible. They've had to dive into archives and pull out old documents to figure out things like, what language does this machine even speak?

Not everyone who used to work on ISEE-3 is still around.

James Green is now director of the planetary science division at NASA headquarters. When he was in his 30s, he set up a state-of-the-art computer network to help researchers quickly get their data during the spacecraft's comet mission. He recently sat in his office, reviewing a list of the spacecraft's science instruments and the researchers who were in charge of them, way back when.

"Keith Ogilvie's here, I'm sure he's retired. ... Smith is retired. ... Jean-Louis Steinberg, I believe he's retired," says Green, running down the list. "Bonnard Teegarden — he's retired many years ago."

Another problem is that some of the old equipment needed to talk to the spacecraft is just ... gone. NASA got rid of it when systems were modernized, says Green, who explains that "deep space communication has changed radically over the last 25 years."

But it looks like an 18-meter satellite dish at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory still has the right hardware. "And so NASA has given them the approval to be able to try that out," Green says.

Workers there are trying to see how well they can communicate with the spacecraft and assess its condition. This is still a kind of unofficial effort, however, because NASA managers haven't made any firm commitment to this spacecraft — despite Farquhar's relentless lobbying.

"You know, Bob Farquhar is a man of his word. If he said he would do everything he could — because he's borrowed the spacecraft — to put it back, that's what he's going to try to do," Green says.

He says Farquhar is a legendary figure around NASA. "We owe a lot to Bob's creativeness to get our spacecraft in locations that we want them," he says. "And so from that perspective he's really a neat guy, really important in our field."

Meanwhile, Farquhar isn't optimistic that this particular spacecraft will end up where he wants it.

"Well, I think the chances are, oh, 50-50," he says.

When he recently sat down at home to talk about his quest, he was wearing plaid flannel pajamas and a robe because he wasn't feeling well. Still, he spoke for nearly two hours.

"It's the most cost-effective spacecraft we ever had and I'd like to make it even more cost-effective. It can do more missions," says Farquhar.

But only if a command is sent soon, by late May or early June. This is his last chance.

If ISEE-3's path doesn't change, it will fly by the Earth and the moon in August. David Dunham of KinetX Aerospace, Inc., one of Farquhar's long-time collaborators, says the encounter will change its orbit. The spacecraft will swing back toward Earth again in about 15 years, but it won't be close enough to recapture.

"If we miss this time, then it just would be too far from the Earth," says Dunham. "I haven't looked — maybe sometime two centuries from now it might come close enough to the Earth again."

But at that point, Dunham says, who knows if the spacecraft would still be alive.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAyNDY5ODMwMDEyMjg3NjMzMTE1ZjE2MA001))