Tampa was once considered the cigar capital of the world.

Cigar rolling peaked in the city in the 1920s. In the '70s and '80s, the industry largely moved to Latin America, where labor was cheaper.

As tides changed, hundreds of cigar factories, businesses and other buildings were left vacant in West Tampa and Ybor City.

Some fell into disrepair.

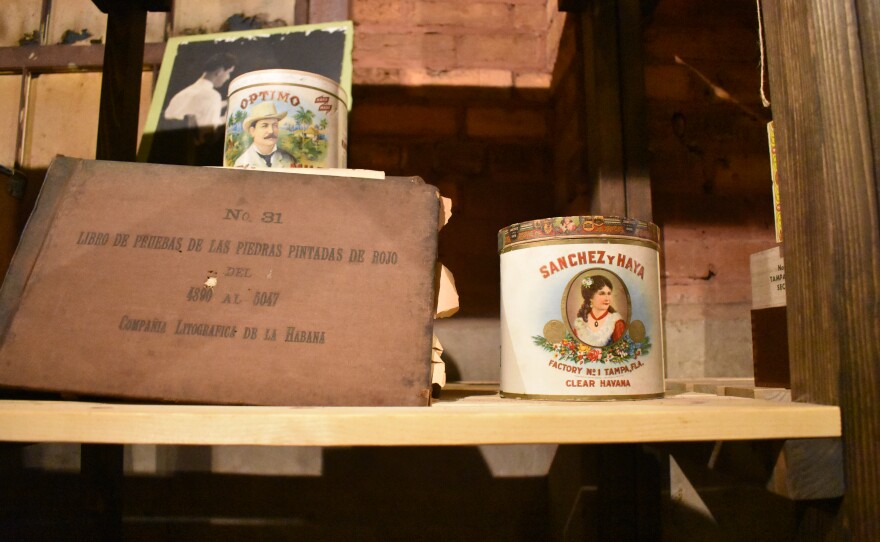

One of them — the Sanchez y Haya building, in the Ybor City Historic District — is being restored to its former glory.

Historic gathering place for cigar workers

The 115-year-old building, at Columbus Drive and 16th Street, is entering the final phase of an $18.7 million restoration project.

It’s expected to be completed by October.

ALSO READ: Renovation will begin on the historic Ybor City Sanchez y Haya building

Spearheading the effort are the owners of the J.C. Newman Cigar Co., whose El Reloj factory sits directly across Columbus Avenue. El Reloj, or "The Clock" in Spanish, is widely considered the country's last traditional cigar factory still in operation.

Drew Newman, the fourth-generation owner of the 130-year-old company, said the buildings have a shared history.

"Our El Reloj cigar factory opened on March 31, 1910, and the Sanchez y Haya building opened a few months later. The buildings were built independently, but ... they were designed to work together,” he said.

The Sanchez y Haya building — once a 15-room hotel, cigar lounge and cafe — was a popular gathering spot for cigar workers more than a century ago.

It was built by Ignacio Haya — the first man to roll cigars in Tampa — and his business partner, Serafin Sanchez.

Since then, it’s taken many forms — a grocery store, a coffee mill, a knitting store and even a Prohibition-era speakeasy — before falling into decline, according to the city.

In 2020, the Newman family bought the adjacent building for $650,000 with the intention of restoring it to its original purpose.

Local, state and federal partners are investing in the vision, too.

The project recently received a $5 million grant from the East Tampa Community Redevelopment Agency, a $600,000 historic preservation grant from Hillsborough County and a $2.3 million federal tax credit from the National Park Service, according to the budget summary.

Once complete, Newman hopes the building will enshrine an important chapter in Tampa’s history — one that earned it the nickname of “Cigar City.”

How Tampa became Cigar City

During the heyday of the cigar industry in Tampa, there were about 200 factories, like El Reloj, producing more than 700 million cigars a year.

“Cigars are to Tampa, just like cars are to Detroit and wine is to Napa Valley. Cigars are so important to the history of our community because it was the cigar industry that fueled Tampa's economy and its growth from a tiny village into the city that it is today,” Newman said.

Between 1880 and 1930, the population jumped from about 700 to more than 100,000.

Many of them were immigrants from Cuba, Spain, Italy and Germany who came to work in Tampa’s burgeoning cigar industry.

"When Mr. Ybor decided to come to Tampa in 1885 the rest of the cigar industry followed, and Tampa was filled with waves of immigrants from all around the world,” Newman said.

Vincente Martinez Ybor, for whom Ybor City is named, is revered as the godfather of the cigar industry in Tampa. However, Haya and Sanchez opened the first cigar factory, Sanchez y Haya Co., at Seventh Avenue and 15th Street, and began production in 1886.

In 1910, they opened the hotel and cafe.

Keeping the legacy alive

More than a century later, the building is getting new life.

Last week, local leaders, cigar workers and other community members gathered for a groundbreaking ceremony at the historic site.

Christian Klein, a descendant of Sanchez, was there to witness the big moment in his family’s history.

“We’re standing … in the shadow of a building from 1910 that my great-great-grandfather built to support the cigar workers … and now the Newman family is continuing and restoring it, which is great,” he said.

Klein said it feels like a full-circle moment to witness the owners of the last traditional operational cigar factory in the country restore his family’s building.

Newman said it’s been a long process to get to this point.

This has included purchasing the building, securing financing, reinforcing the integrity of the concrete-and-rebar structure and even rehoming 5,000 fruit bats.

“It would have been far easier and cheaper and faster to knock the Sanchez y Haya building down and build a replica of it in its place, but I was afraid doing so would cause us to lose the building's character and spirit and history,” he said.

Like the cigar-rolling process, Newman said doing things right takes time.

Gabriella Paul covers the stories of people living paycheck to paycheck in the greater Tampa Bay region for WUSF. Here’s how you can share your story with her.